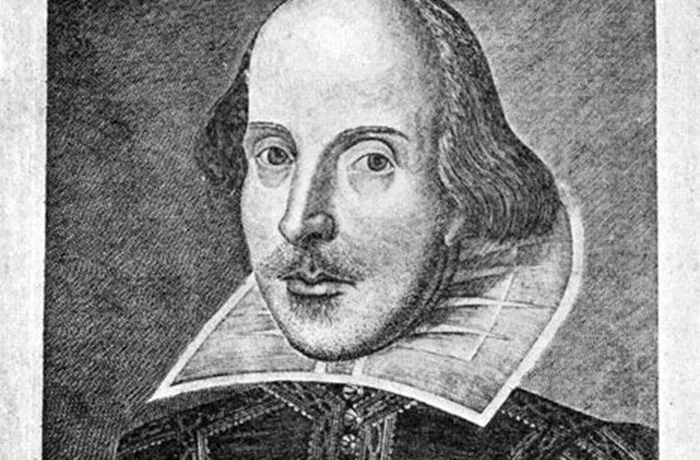

Sonnets are a type of poem that have been around for centuries. They are known for their strict structure and specific rules that make them unique. Many famous poets, including William Shakespeare, John Keats, and Petrarch, have written sonnets that continue to be admired today. Understanding sonnets can be both exciting and a little challenging because they have certain patterns and rules that must be followed. But don’t worry, once you break it down into smaller parts, it’s easy to see why sonnets are such a popular and respected form of poetry.

In this article, we’ll explore the three main requirements for a sonnet. These requirements help give the sonnet its distinct shape and rhythm. Whether you’re a budding poet or just someone who loves reading poetry, knowing these rules will help you understand what makes a sonnet a sonnet.

What is a Sonnet?

Before diving into the three main requirements of a sonnet, it’s important to understand what a sonnet is. A sonnet is a poem made up of 14 lines. The lines are usually written in a specific meter, often iambic pentameter, and follow a particular rhyme scheme. Though the structure may sound complex, it’s part of what makes the sonnet so effective at expressing deep emotion, philosophical thoughts, or capturing moments of beauty.

Sonnets are often divided into two major categories: the Italian sonnet (or Petrarchan sonnet) and the English sonnet (or Shakespearean sonnet). Both have their own rules, but they share one thing in common—the focus on the 14 lines. Each type of sonnet uses its own rhyme scheme and thematic division, but the structure and meter remain consistent throughout.

The Three Requirements for a Sonnet

To write a proper sonnet, you need to focus on three main things: the number of lines, the meter, and the rhyme scheme. Let’s break these down one by one.

1. 14 Lines

A sonnet must always have 14 lines. This is perhaps the most defining feature of a sonnet. The number 14 is not flexible—if the poem has more or fewer lines, it’s no longer considered a sonnet.

The 14 lines are typically divided into two sections:

The octave: This is the first eight lines of the sonnet.

The sestet: This is the last six lines of the sonnet.

The octave often introduces a problem, idea, or question, while the sestet provides a resolution or response to the octave. This division is especially clear in the Italian sonnet. In the English sonnet, the 14 lines are broken up into three quatrains (four-line sections) followed by a final couplet (a two-line section). The break between the octet and sestet (or quatrains and couplet) is important for the flow of ideas and emotions in the poem.

The 14-line structure of a sonnet allows the poet to develop a complete thought or argument within a short space. It gives the poem a sense of compactness and unity, while still leaving room for exploration and expression.

2. Meter: Iambic Pentameter

Meter refers to the rhythm of a poem—the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables that create its flow. Most sonnets are written in a meter called iambic pentameter. This is a type of meter where each line has ten syllables, and the syllables alternate between unstressed and stressed. It’s called “iambic” because of the pattern of unstressed and stressed syllables (da-DUM), and “pentameter” because there are five feet (or pairs of syllables) in each line.

For example, this line from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 is written in iambic pentameter:

“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”

Let’s break it down:

Shall I (unstressed, stressed)

compare (unstressed, stressed)

thee to (unstressed, stressed)

a sum- (unstressed, stressed)

mer’s day (unstressed, stressed)

Each of the five pairs of syllables follows the iambic pattern, creating a rhythmic flow. Writing a sonnet in iambic pentameter can be a bit tricky at first, but once you get the hang of it, it gives the poem a musical quality that’s part of what makes sonnets so appealing.

While iambic pentameter is the most common meter for sonnets, it’s not always strictly followed. Poets may sometimes use variations or break the pattern for emphasis or stylistic effect, but the general rule is to stick to the iambic pentameter as much as possible.

3. Rhyme Scheme

The rhyme scheme is another important element of a sonnet. It refers to the pattern of rhymes at the end of each line. In a sonnet, the rhyme scheme must be regular and consistent, and different types of sonnets have different rhyme schemes.

There are two main types of sonnets: the Italian (or Petrarchan) sonnet and the English (or Shakespearean) sonnet. Let’s explore their rhyme schemes:

Italian Sonnet (Petrarchan Sonnet)

The rhyme scheme for the Italian sonnet is ABBAABBA for the first eight lines (the octave) and CDCDCD or CDECDE for the last six lines (the sestet). The rhyme scheme creates a sense of harmony in the first eight lines, with a shift in the sestet to introduce a new thought or resolution.

Here’s an example from Petrarch’s sonnet:

“Upon the breeze my soul was always soaring, (A)

And now it seeks to rest in your embrace (B)

So that, in love, it may forever race (B)

Until it finds the peace that it is adoring. (A)

The wind is silent, and my heart is stirring (A)

To find its way towards a tender grace. (B)

And when I reach it, I will find my place (B)

And know the love that I have been imploring.” (A)

This sonnet’s first eight lines follow the ABBAABBA rhyme scheme, and the last six lines shift to a new pattern, typical of the Petrarchan style.

English Sonnet (Shakespearean Sonnet)

The rhyme scheme for the English sonnet is ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. The first twelve lines are divided into three quatrains, and the final two lines form a rhymed couplet. The rhyme scheme allows for a buildup of ideas in the first three quatrains, with the couplet providing a resolution or dramatic twist.

Here’s an example from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18:

“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? (A)

Thou art more lovely and more temperate: (B)

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, (A)

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date: (B)

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, (C)

And often is his gold complexion dimm’d; (D)

And every fair from fair sometime declines, (C)

By chance or nature’s changing course untrimm’d; (D)

But thy eternal summer shall not fade (E)

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st; (F)

Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade, (E)

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st; (F)

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, (G)

So long lives my love, and my love lives on in thee.” (G)

The rhyme scheme here follows the ABAB CDCD EFEF GG pattern, which is typical for the Shakespearean sonnet. The rhymes provide a musical flow and support the poet’s expression of love and immortality.

Conclusion

Writing a sonnet might seem daunting at first due to its specific structure, meter, and rhyme scheme. However, once you understand the three essential requirements—a strict 14-line structure, the use of iambic pentameter, and a clear rhyme scheme—you’ll begin to see why sonnets are such a powerful form of poetry. These elements help convey a poet’s emotions and ideas in a concise and beautiful way.

Whether you choose to write an Italian or an English sonnet, remember that the key to mastering sonnets is practice. Start by following the rules closely, and as you gain confidence, feel free to experiment with variations and explore new creative ideas. Writing sonnets allows poets to engage with timeless themes—love, nature, time, and beauty—and express complex emotions with simple yet profound language.

So, the next time you come across a sonnet, you’ll be able to appreciate not just the beauty of the words but also the structure and craftsmanship that go into creating such an elegant piece of poetry.