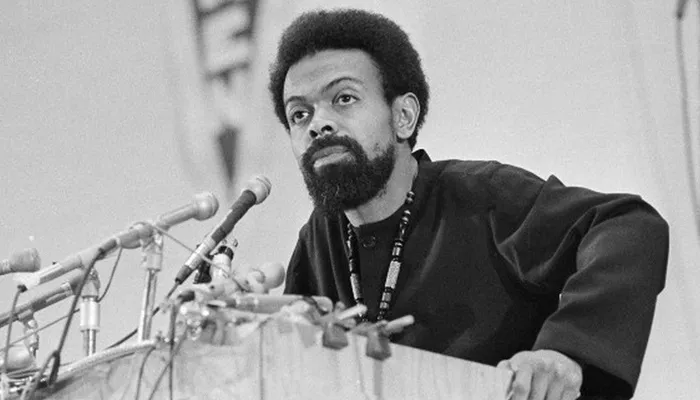

Amiri Baraka, born Everett LeRoi Jones in 1934, is a significant figure in 20th-century American poetry. His works cover various themes such as race, politics, culture, and personal identity, offering a unique perspective on the African American experience in America. Baraka is often considered one of the most powerful and provocative poets of the 20th century, renowned for his vivid, sometimes controversial language and his passionate exploration of the complexities of life in America.

Early Life and Influences

Amiri Baraka’s early life in Newark, New Jersey, shaped much of his later work. Growing up in an urban environment, Baraka was exposed to the struggles of the working class, African Americans, and the pervasive issues of race and inequality that would later form the foundation of his literary career. Baraka’s youth was marked by an awareness of the racism and segregation that existed in American society, particularly in the North, which differed from the more overt racial issues in the South. His upbringing during the Civil Rights Movement profoundly impacted his views on social justice, race relations, and the need for change.

Baraka’s academic journey began at Howard University, a historically Black college, where he was introduced to the intellectual currents and racial consciousness that would influence his work. He later studied at the University of Harlem, where he encountered both classical and modern European and American poets, including William Blake, William Wordsworth, and T.S. Eliot. However, it was the African American poets of the Harlem Renaissance, particularly Langston Hughes and Claude McKay, whose work resonated most deeply with Baraka’s emerging voice.

Baraka’s early work as a poet was heavily influenced by his experiences with race and politics in America. His exposure to the ideas of Marxism, as well as his time spent in Cuba and other parts of the Caribbean, provided him with the tools to explore issues of oppression, revolution, and resistance through his writing. These themes would dominate much of his work throughout his career.

The Early Years: From “Poet” to “Revolutionary”

In the 1950s and early 1960s, Baraka was heavily involved in the Beat movement, and his early poetry reflected his association with the avant-garde literary scene. His first collection, Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note (1961), explored themes of isolation, despair, and personal identity, reflecting the disillusionment of the era. The poems in this collection feature a deeply introspective tone, marked by a modernist sensibility and an exploration of individual alienation in a rapidly changing world.

During this period, Baraka’s poetry was rooted in the avant-garde traditions of modernism, blending jazz, blues, and the rhythms of African American culture into his verse. His writing also took on an experimental form, with fragmented images and disjointed language that sought to evoke emotional truths rather than represent rational ideas. Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note was just the beginning of Baraka’s literary career, which would later transition into more politically driven work.

By the mid-1960s, Baraka had fully embraced revolutionary politics, which significantly changed the direction of his poetry. This shift coincided with his departure from the Beat movement and his increasing involvement with the Black Power movement. Baraka’s later work reflects a more militant stance, and he began to associate himself more with the Black Nationalist movement and the civil rights struggles of the time.

In 1965, Baraka’s name change from LeRoi Jones to Amiri Baraka symbolized his break with his past as a poet and his embrace of a more radical political and cultural identity. Baraka’s decision to take a new name also signified his rejection of the white-dominated literary world and his commitment to a Black aesthetic that was rooted in the traditions of African American culture. This change was reflected in his poetry, as his work began to focus more on social issues, specifically the plight of African Americans in a segregated and racist society.

Political Poetry and the Rise of Black Nationalism

Amiri Baraka’s move towards political poetry culminated in his most famous and influential collection, The Dead Lecturer (1964). This work marked a departure from his earlier Beat-influenced poetry, embracing a more direct, confrontational style. The poems in The Dead Lecturer challenge the dominant narratives of white American society, emphasizing the need for Black people to assert their own identity, culture, and political power. Baraka’s writing during this period was heavily influenced by the rise of Black Nationalism and the work of leaders like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael, who advocated for Black self-determination and empowerment.

Baraka’s political poetry gained further prominence in the 1960s with the publication of Blues People: Negro Music in White America (1963), a groundbreaking work of cultural criticism. In this book, Baraka explores the history of African American music and its role in shaping both Black culture and American culture at large. Baraka argues that the development of jazz, blues, and other forms of African American music was a direct response to the historical oppression and disenfranchisement of Black people. The book became a significant contribution to the cultural revolution of the 1960s, offering a new way of understanding the role of African American art and culture in the larger context of American society.

Baraka’s commitment to political activism also led him to become more involved in the Black Arts Movement, a cultural and artistic movement that sought to redefine African American identity through literature, visual art, and performance. As the founder of the movement’s flagship journal, The Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School, Baraka helped shape the discourse around Black art and its role in the struggle for racial justice. His work during this period focused on the need for Black artists to create literature that was unapologetically political and socially engaged.

The Later Years: From Black Nationalism to Cultural Criticism

As the 1970s unfolded, Baraka’s political beliefs evolved, and his work became increasingly focused on issues of class, gender, and cultural identity. During this time, Baraka became a vocal critic of both American imperialism and the capitalist system. He also became more critical of traditional forms of African American art, especially as the mainstream media and white institutions began to co-opt Black cultural expression for commercial purposes.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Baraka’s writing shifted towards an exploration of the intersection of race and politics, as well as the role of African American intellectuals in shaping public discourse. His later poetry often incorporated elements of satire, cultural criticism, and social commentary, offering a sharp critique of the status quo. His collection The Autobiography of LeRoi Jones (1984) reflects this shift, as it focuses on Baraka’s personal evolution from a politically conscious poet to a more complex figure, grappling with his changing views on race, class, and politics.

Despite the controversy that sometimes surrounded his work, particularly due to his unapologetic support of Black Nationalism and his critique of white America, Baraka’s contributions to American poetry cannot be overstated. His works stand as both a reflection of the African American experience and a challenge to the cultural and political institutions that have historically marginalized Black voices.

Comparison with Other 20th Century American Poets

Amiri Baraka’s work, especially his political and revolutionary poetry, places him in direct conversation with other 20th-century American poets such as Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Robert Hayden. Each of these poets grappled with themes of race, identity, and the complexities of American life, but Baraka’s approach was often more radical and confrontational.

Langston Hughes, for example, is often seen as the quintessential poet of the Harlem Renaissance, whose work emphasized the beauty and resilience of African American culture. While Hughes was concerned with racial justice, his poetry was more focused on celebrating Black life than critiquing the institutions of American society. In contrast, Baraka’s poetry was much more politically charged, demanding not only recognition but also a radical transformation of the racial dynamics in America.

Similarly, Gwendolyn Brooks, a renowned poet from Chicago, focused on the inner lives of African Americans, particularly in her depiction of urban life. While Brooks’s poetry also dealt with issues of race and class, she employed a more subtle and nuanced approach than Baraka, whose work was characterized by its forceful, direct language and its call to action.

Baraka’s poetry also sets him apart from more traditional American poets, such as Robert Frost and Wallace Stevens, who focused on nature, existentialism, and philosophical themes. In contrast, Baraka’s work is firmly rooted in the political and cultural issues of his time, reflecting the urgency and complexity of the social movements that defined the 1960s and 1970s.

Conclusion

Amiri Baraka’s legacy as a 20th-century American poet is marked by his unflinching commitment to political activism, his bold exploration of race and identity, and his role in shaping the course of African American literature. His work continues to inspire generations of poets, writers, and activists who seek to challenge the status quo and give voice to marginalized communities. Baraka’s contribution to American poetry is invaluable, as it reflects not only the struggles of Black Americans but also the larger cultural and political shifts that defined the 20th century. Through his poetry, Baraka carved out a space for revolutionary voices in American literature, making him one of the most influential poets of his time.