The 19th century was a golden age for British poetry. It witnessed the rise of literary titans such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Robert Browning, and Matthew Arnold. In the rich landscape of Romantic and Victorian verse, the name William Allingham is not often placed among the most illustrious. Yet, Allingham’s work possesses a lyrical charm and folkloric sensibility that contributed uniquely to 19th Century British poetry. A native of Ireland and a British poet by vocation, Allingham occupies a quiet but crucial position in the period’s literary history. His poetry reflects a pastoral vision, a childlike curiosity, and a devotion to the natural and mythical world.

This article aims to examine the life, works, themes, and literary context of William Allingham. In doing so, it seeks to situate him within the broader framework of 19th Century British poets, offering comparisons and contrasts to illuminate his artistic contribution. By exploring the intersections between his poetry and that of his contemporaries, we can better appreciate the significance of this often-overlooked figure in the evolution of British poetry.

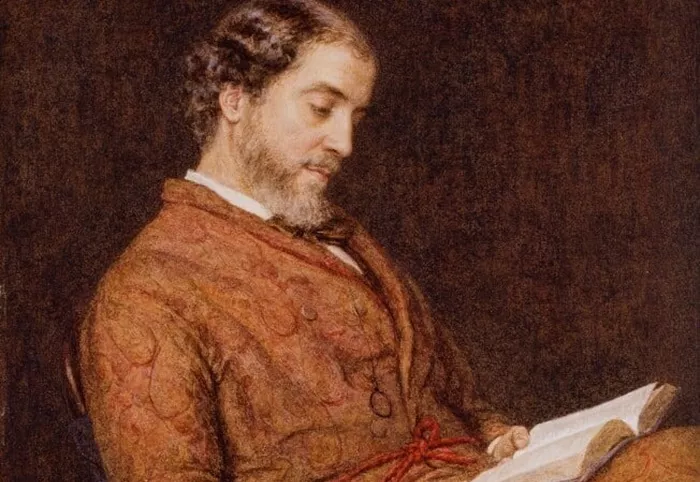

William Allingham

William Allingham was born on March 19, 1824, in Ballyshannon, County Donegal, Ireland. His upbringing in a coastal Irish town surrounded by folklore, rustic life, and Celtic traditions played a formative role in shaping his poetic imagination. Although Irish by birth, Allingham’s work is primarily considered a part of British poetry due to his integration into the literary circles of London and his service under the British government.

His early education was limited, but he developed a passion for literature. The writings of William Wordsworth, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Thomas Moore had a lasting influence on him. Wordsworth’s attention to rural life and simple subjects resonated with Allingham’s aesthetic sensibilities, while Shelley’s ethereal vision and Moore’s melodic lyrics inspired his approach to poetic form.

At the age of fourteen, Allingham became a customs officer, a position that offered him financial stability but little artistic fulfillment. Despite this, he continued to write poetry, and in 1850, he published his first major work, Poems. This volume received modest attention but marked the beginning of a serious literary career.

Thematic Landscape: Folklore, Nature, and the Spirit World

One of the most distinguishing features of William Allingham’s poetry is his preoccupation with folklore and the supernatural. Unlike many of his contemporaries who focused on industrialization, politics, or philosophy, Allingham returned repeatedly to themes of childhood, fairy tales, and the mysterious landscapes of nature.

His most famous poem, The Fairies, illustrates this aspect of his work:

“Up the airy mountain,

Down the rushy glen,

We daren’t go a-hunting

For fear of little men…”

These lines have become emblematic of Allingham’s style—simple, musical, and steeped in the imagination of the countryside. The poem captures both the beauty and the eerie dangers of the supernatural world, reflecting the deep roots of Celtic myth in his worldview. While not as philosophically dense as Matthew Arnold or as technically innovative as Robert Browning, Allingham’s poetry taps into a collective cultural memory that was being threatened by the encroaching modern world.

His love of nature is another constant. Poems such as Robin Redbreast and Day and Night Songs reveal an intense sensitivity to the rhythms of the natural world. His use of visual imagery is vivid yet unpretentious. Where Tennyson might evoke grandeur and solemnity, Allingham offers intimacy and quiet observation.

Literary Style: Simplicity and Song

Allingham’s poetry is characterized by a simplicity of language that belies its depth. He often employed short lines, regular meter, and end-rhyme schemes that evoke traditional ballads and nursery rhymes. This stylistic approach made his work accessible and memorable, particularly for younger readers.

This accessibility, however, sometimes led critics to underestimate the sophistication of his craft. While Allingham did not engage in the psychological drama found in Browning’s monologues or the religious speculation seen in Arnold, he achieved a different kind of poetic success. He preserved the oral tradition in British poetry by weaving songs that resonated with the musicality of an earlier age. This preservation was, in itself, a literary act of resistance against the mechanization of culture.

His editorial work also reflects this aesthetic. As editor of Fraser’s Magazine from 1874 to 1879, he promoted not only high literature but also lighter verse and experimental forms. His literary taste was broad, and his inclusive sensibility helped foster a more diverse poetic environment.

Comparisons with Contemporaries

To better understand Allingham’s position within 19th Century British poetry, it is useful to compare his work with that of his more well-known contemporaries.

Tennyson and the Romantic Legacy

Alfred, Lord Tennyson, the Poet Laureate of Great Britain, was the dominant voice of Victorian poetry. His works, such as In Memoriam A.H.H. and The Idylls of the King, exemplify the grand scope and formal mastery of the age. While Tennyson dealt with themes of loss, empire, and faith, Allingham’s poems focus more on individual sensation, memory, and folklore.

Both poets were influenced by the Romantic tradition, particularly Wordsworth and Coleridge, but Allingham retained more of the Romantic focus on nature as a living, enchanted force. In contrast, Tennyson’s treatment of nature often serves as a backdrop for moral or philosophical reflection.

Robert Browning and Psychological Complexity

Robert Browning is celebrated for his dramatic monologues and the psychological depth of his characters. His poetry is dense, intellectual, and often challenging. Allingham’s style could not be more different. He avoids complex syntax and abstract ideas in favor of lyricism and clarity. However, this simplicity should not be mistaken for naivety. Where Browning explores the mind, Allingham explores the spirit, particularly as it manifests in children and rural life.

Christina Rossetti and Devotional Lyricism

Christina Rossetti is perhaps the closest kindred spirit to Allingham among the 19th Century British poets. Both writers exhibit a musical lyricism and a deep connection to spirituality. However, Rossetti’s work is more explicitly Christian and often marked by themes of renunciation and divine love. Allingham, on the other hand, leans more toward the mystical and folkloric.

Rossetti’s Goblin Market shares with Allingham’s The Fairies a fascination with mythical creatures and moral undertones. Both poems can be read as allegories of temptation and innocence, although their respective tones—Rossetti’s being darker and more allegorical—highlight different artistic priorities.

Personal Life and Later Years

In 1874, Allingham married Helen Paterson, an accomplished illustrator and watercolorist. She would later become known as Helen Allingham, famous for her paintings of idyllic English country scenes. The couple had three children and enjoyed a peaceful domestic life in Surrey. Helen’s artistic vision complemented William’s literary world, and their collaboration enriched both of their creative outputs.

William Allingham retired from his editorial duties in 1879, spending his final years in relative quiet. He died in 1889 and was buried in Hampstead, London. Although he never achieved the fame of his peers, his poetry remained in print, and his influence lived on, especially among those drawn to the folkloric tradition in British poetry.

Legacy and Reception

While William Allingham is often considered a minor figure in the grand narrative of 19th Century British poetry, his work has been rediscovered in recent decades by scholars interested in folklore, children’s literature, and the oral tradition. His journals, published posthumously as The Diaries of William Allingham, offer invaluable insights into the literary and cultural milieu of Victorian Britain. They include accounts of his interactions with figures such as Carlyle, Rossetti, and Tennyson, offering readers a unique behind-the-scenes look at the period’s intellectual life.

Allingham’s poetry has also found renewed interest in studies of Anglo-Irish literature. Although he wrote within the framework of British poetic tradition, his sensibility and subject matter remain deeply rooted in Irish culture. This dual identity adds a layer of complexity to his legacy. He stands as both a British poet and an Irish voice, bridging the two literary traditions at a time when political tensions between them were intensifying.

Conclusion

William Allingham may not command the same scholarly attention as Tennyson or Browning, but his poetry deserves recognition for its charm, sincerity, and cultural resonance. As a 19th Century British poet, Allingham enriched British poetry with a distinct perspective—one that valued simplicity over grandeur, myth over reason, and melody over rhetoric.

In an era often dominated by the spectacle of empire and the complexities of industrial society, Allingham’s poetry reminds us of the quiet pleasures of nature, the enchantment of folklore, and the unassuming beauty of lyrical expression. His work stands as a testament to the enduring power of imagination, and his legacy continues to whisper through the pages of British poetry, like the fairies of his most beloved verse—elusive, magical, and quietly profound.