William Shakespeare, regarded as one of the greatest writers in the English language, is a figure whose legacy continues to shape literature, theater, and even modern thought. However, while his work is universally acknowledged, his personal life and the details of his final years remain subjects of deep curiosity and scrutiny. One of the most intriguing aspects of his personal history is the changes he made to his will.

Shakespeare’s will is notable not only for the bequests it contains but also for the revisions he made to it in the years before his death in 1616. These changes have led to significant questions about Shakespeare’s relationships, his financial status, and the way he envisioned his legacy. Why did Shakespeare change his will, and what do these changes reveal about him as a person? To answer these questions, we need to look at the historical context of Shakespeare’s life, the people close to him, and the cultural and social pressures that may have influenced his decisions.

The Creation of Shakespeare’s First Will

Shakespeare’s will was first written on March 25, 1596, in a document that has survived to this day. At the time, Shakespeare was an established playwright in London, although he had not yet achieved the level of fame and fortune that would come later in his career. The early will reveals a man who was beginning to gain recognition and wealth, but whose personal circumstances were still evolving.

At this point, Shakespeare had been married to Anne Hathaway for several years. The couple had three children: Susanna, who was born in 1583, and twins Hamnet and Judith, born in 1585. Shakespeare’s will from 1596, however, does not indicate any great concern for his wealth or legacy; it is relatively straightforward. His primary bequest was to his wife, Anne, who was given the bulk of his property and assets in the event of his death.

The will also outlined provisions for his children, with a clear emphasis on ensuring that they were well provided for. However, it was relatively simple and lacked the complexity seen in his later wills, particularly when it came to matters of inheritance and personal relationships.

Shakespeare’s Return to Stratford and the Final Will

By the time Shakespeare wrote his final will in 1616, his life had undergone several significant changes. After years of success in London, Shakespeare retired from the theater and returned to his hometown of Stratford-upon-Avon, where he lived in relative comfort. His wealth had increased, and he was no longer merely a playwright and actor, but also a landowner and a respected figure in his community.

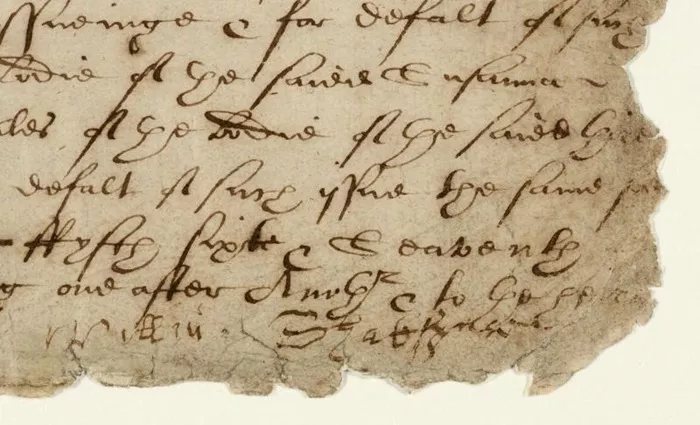

This period of his life marks a significant departure from the earlier years of his career, and his final will reflects these changes. Written on March 25, 1616, shortly before his death, the will is more detailed and far more significant than his earlier testament. It provides a glimpse into Shakespeare’s financial success, his changing views on family, and his desire to control the distribution of his assets.

The final will, which has survived in its entirety, is a much more structured and complicated document. Shakespeare made specific bequests to his daughters, Susanna and Judith, and left the bulk of his estate to his eldest daughter, Susanna. However, the most notable change in this will is the bequest of his “second-best bed” to his wife, Anne Hathaway.

The Bequest of the “Second-Best Bed”

The most famous part of Shakespeare’s final will is the bequest of his “second-best bed” to his wife, Anne. The wording of this particular bequest has led to numerous debates among scholars and historians, with many interpreting it as an indication of Shakespeare’s complex feelings toward his wife.

At the time of his death, Anne Hathaway was likely in her early sixties, and her marriage to Shakespeare had been a long one. They had been married in 1582, when Shakespeare was just eighteen years old. While it is not uncommon for husbands to leave personal items to their wives in their wills, the decision to leave Anne only the second-best bed has been seen by some as a sign of Shakespeare’s coldness or neglect toward her. Others argue that it was simply a practical decision, as the second-best bed would likely have been the most comfortable and well-appointed piece of furniture in the household.

However, there are alternative explanations. Some scholars suggest that the bequest of the second-best bed was a symbolic gesture, indicating that Shakespeare wished to leave something of personal value to Anne, but also wanted to ensure that his other assets were distributed according to his wishes. The bed, in this case, might have represented a gesture of intimacy or a way of acknowledging their shared life together, rather than a reflection of any lack of affection.

Regardless of its exact meaning, the bequest of the second-best bed has become one of the most discussed aspects of Shakespeare’s final will and has contributed to the mystique surrounding his relationship with his wife.

The Role of Shakespeare’s Daughters in His Will

Shakespeare’s final will also highlights the important role his daughters played in his life. As mentioned, the bulk of his estate was left to his eldest daughter, Susanna. In addition to her inheritance, Susanna was named as the executor of Shakespeare’s estate, a position of great responsibility that would have required her to manage the distribution of her father’s wealth and property.

Shakespeare’s decision to leave a significant portion of his estate to Susanna reflects the close relationship they shared. Susanna was, by all accounts, a highly intelligent and capable woman. She had married John Hall, a respected physician, in 1607, and the couple had a child, making Shakespeare a grandfather by the time of his death. The choice to leave Susanna in charge of his estate indicates that Shakespeare had a great deal of trust in her abilities.

In contrast, his relationship with his younger daughter, Judith, seems to have been more complicated. While she was also included in the will and given a portion of her father’s estate, Judith’s share was somewhat less than that of her sister Susanna. Judith had married Thomas Quiney, a man who was not widely respected in the community, and Shakespeare’s bequests to her seem to reflect a degree of concern about her future well-being. In fact, Judith’s inheritance was contingent upon the survival of her marriage, and if she had died without issue, her portion of the estate would have been passed on to her sister.

This aspect of Shakespeare’s will reveals his desire to ensure that his family was cared for, but it also highlights the complicated nature of his relationships with his children. Shakespeare’s trust in Susanna was clear, but his feelings toward Judith were more ambivalent, as evidenced by the stipulations surrounding her inheritance.

The Historical Context of Shakespeare’s Will

The changes Shakespeare made to his will must be understood within the broader historical context of his life and times. The early 17th century was a period of great social and political change in England, and Shakespeare was not immune to these pressures. In addition to the personal dynamics within his family, Shakespeare’s will was shaped by the legal and financial realities of the time.

During Shakespeare’s life, inheritance laws were complex and could lead to disputes over property and wealth. In the absence of a male heir, Shakespeare’s decision to leave the majority of his estate to Susanna would have been a way of ensuring that his wealth remained within the family. Furthermore, the practice of leaving personal items like the second-best bed to one’s wife was common in the 16th and 17th centuries, though it has taken on greater significance in Shakespeare’s case due to the lack of any other major bequests to Anne.

The social expectations of the time also played a role in shaping Shakespeare’s will. As a respected member of the Stratford community, Shakespeare would have been under pressure to ensure that his family was provided for, particularly after his death. The fact that he made provisions for his daughters, including the conditional inheritance for Judith, suggests that he was acutely aware of the importance of securing his family’s financial future in a period where women had limited control over property.

Conclusion

In the years since his death, Shakespeare’s will has become a subject of enduring fascination. The revisions he made to his will provide a glimpse into his evolving relationships with his family, his views on wealth and inheritance, and his desire to control the distribution of his estate after his death. While the bequest of the second-best bed to his wife has sparked debate about Shakespeare’s feelings toward her, it also serves as a powerful reminder of the complexities of his personal life.

Shakespeare’s will is a document that reflects the tensions between public and private life, between artistic legacy and family obligation. It reveals a man who, despite his fame and fortune, was still deeply concerned about his family and the future of his estate. Ultimately, Shakespeare’s final will serves as a key to understanding his life beyond the stage and offers a reminder that even the greatest minds are shaped by the same human concerns that influence all of us.