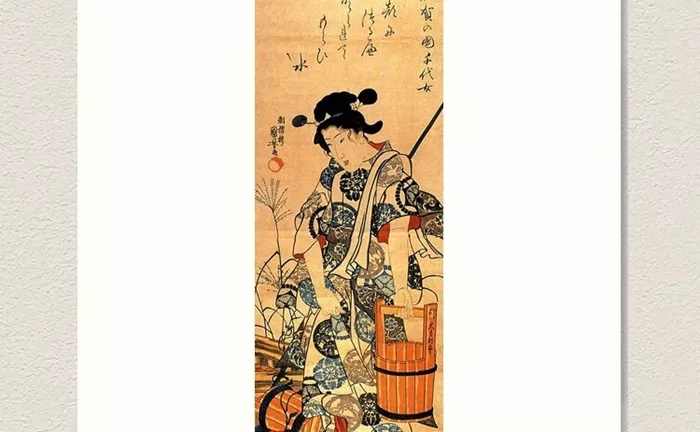

[pb]1[/pb] (1703–1775) stands as one of the most influential and celebrated figures in 18th-century Japanese poetry. As a haiku poet, her work remains an essential part of the historical and cultural landscape of Japanese literature. In an era of flourishing literary activity, Chiyo’s contributions have significantly shaped the haiku tradition, making her one of the most distinguished 18th-century Japanese poets. Despite the challenges faced by women in 18th-century Japan, Chiyo not only overcame these barriers but also achieved a level of poetic mastery that earned her admiration across generations. This article explores her life, her poetic style, and her place within the broader context of 18th-century Japanese poetry, comparing her work with that of her contemporaries.

Early Life and Background

Kaga no Chiyo, originally born as Chiyo-ni, hailed from the Kaga province (modern-day Ishikawa Prefecture) in Japan. She was born into a time of great literary development during the Edo period, when haiku and other forms of Japanese poetry were widely practiced. Chiyo’s family life is shrouded in some mystery, though it is known that she was born into a family of relatively modest means. As a young woman, she exhibited a remarkable talent for poetry, demonstrating an innate grasp of the haiku form. This early development would set the stage for her future prominence.

While Chiyo’s life was far from easy, her experiences shaped the way she approached her poetry. As was often the case in 18th-century Japan, women were not always given the same opportunities as men in intellectual or artistic circles. Despite these constraints, Chiyo managed to build her reputation as a poet by writing prolifically and engaging with literary groups that valued her work. Much of Chiyo’s poetry is deeply personal and reflective, offering insights into the struggles and challenges she faced as a woman in a male-dominated literary world. Her work stands in stark contrast to the more formal and public-facing poetry of her male contemporaries.

The Haiku Tradition and Chiyo’s Poetic Style

Haiku, the brief but potent form of Japanese poetry, consists of 17 syllables in a 5-7-5 pattern. This form of poetry is often associated with nature, fleeting moments, and deep philosophical themes. As an 18th-century Japanese poet, Chiyo played a pivotal role in shaping and advancing the haiku tradition, which was already being developed and refined by poets like Matsuo Bashō, Yosa Buson, and Kobayashi Issa.

Chiyo’s approach to haiku was deeply influenced by the principles of Zen Buddhism, a tradition that emphasizes mindfulness, simplicity, and an understanding of the transient nature of life. Her poetry often reflects these ideals, focusing on moments of beauty, fragility, and impermanence. Unlike some of her contemporaries who adhered more strictly to formalistic constraints, Chiyo’s haiku often sought to capture raw, intimate experiences, making her poetry accessible and deeply resonant with a broad audience.

One key feature of Chiyo’s work is her use of nature as both a metaphor for human experience and as a subject in itself. Much like Matsuo Bashō, who famously asserted that nature was an essential mirror to the human soul, Chiyo turned to nature as a source of inspiration for her poetry. However, while Bashō’s work often embodies a sense of transcendence, Chiyo’s haiku tend to focus more on the human experience within nature, weaving her own emotions and reflections into the fabric of the natural world.

For example, one of Chiyo’s most famous haiku reads:

“The light of the moon

Still lingers on the flowers—

But it’s almost gone.”

This poem is a beautiful example of Chiyo’s ability to capture the fleeting nature of life. The image of the moonlight lingering on the flowers evokes the transient quality of existence, a theme that is central to many of her poems. The fleeting nature of the moonlight represents the impermanence of beauty and life itself, a core tenet of Buddhist philosophy.

Another signature trait of Chiyo’s haiku is her deftness in conveying complex emotional states through the simplicity of the form. Her ability to express longing, melancholy, and the quiet beauty of nature in a few short lines is what sets her apart from other poets of the period. This emotional depth, coupled with her ability to distill profound experiences into simple yet elegant language, places her in a unique position in the history of Japanese poetry.

Comparison with Other 18th Century Japanese Poets

Kaga no Chiyo’s work exists within a broader context of haiku poetry that was flourishing during the 18th century. This period saw the development of distinct poetic schools and movements, each with its own approach to the haiku form. While Chiyo’s work is undeniably unique, it is also important to understand it in relation to the broader trends and developments in 18th-century Japanese poetry.

One of the most significant influences on Chiyo’s work was Matsuo Bashō, widely considered the greatest haiku poet in Japanese history. Bashō’s emphasis on simplicity, naturalness, and the expression of Zen ideals in his haiku provided a foundation for many later poets, including Chiyo. Like Bashō, Chiyo was inspired by the Zen notion of impermanence and the idea that beauty could be found in the simplest of moments. However, while Bashō’s poetry is often marked by a sense of detachment, Chiyo’s work reflects a more intimate and personal engagement with the world around her.

Another important figure in 18th-century Japanese poetry was Yosa Buson, a poet and painter whose work was heavily influenced by the visual arts. Buson’s haiku often combine vivid imagery with careful attention to the aesthetics of form. While Chiyo’s haiku shares Buson’s sensitivity to the natural world, her poetry tends to focus more on the emotional resonance of nature, rather than the more descriptive, painterly approach that characterizes much of Buson’s work. Chiyo’s poetry conveys the emotional landscape of the human soul in relation to nature, using nature as a reflection of inner states, rather than focusing solely on external descriptions.

Kobayashi Issa, another key poet of the time, also shared a strong connection to nature, but his poetry is more marked by humor, compassion, and a deep sense of empathy for all living things. Issa’s work often speaks to the struggles and suffering of life, emphasizing the interconnectedness of all beings. While Chiyo’s poetry is often more meditative and introspective, she shares with Issa a deep awareness of the transient and fragile nature of life. Both poets, in their own ways, captured the fleeting moments of beauty and pain that define the human experience.

The Legacy of Kaga no Chiyo

Kaga no Chiyo’s legacy as a haiku poet is enduring and multifaceted. Her ability to blend the spiritual with the personal, the natural world with human emotions, has made her one of the most admired figures in Japanese poetry. Her poems, with their simplicity, subtlety, and depth, have influenced countless poets and readers, both in Japan and abroad.

Chiyo’s significance lies not only in her mastery of haiku but also in her role as a woman poet in a male-dominated literary tradition. During the Edo period, women were often excluded from the literary circles that shaped Japanese culture. Chiyo, however, was able to carve out a space for herself in the world of haiku, earning the respect of male poets and establishing herself as a leading figure in the genre. Her work serves as a testament to the resilience and creativity of women in a time when their voices were often marginalized.

In addition to her poetic contributions, Chiyo’s work continues to be an essential part of the study of 18th-century Japanese poetry. Her poems provide valuable insights into the cultural and spiritual climate of the Edo period, reflecting the era’s preoccupation with the fleeting nature of life and the search for inner peace. Her poems remain an important part of the haiku canon, studied by scholars, admired by poets, and appreciated by readers for their simplicity and beauty.

Conclusion

Kaga no Chiyo’s life and work embody the essence of 18th-century Japanese poetry. As a haiku poet, she created a body of work that reflects the impermanence of life, the beauty of nature, and the complex emotional landscape of the human condition. Her poetry stands out not only for its lyrical quality and emotional depth but also for the way it challenges traditional gender roles and establishes Chiyo as a significant voice in Japanese literary history. When compared to her contemporaries, such as Matsuo Bashō, Yosa Buson, and Kobayashi Issa, Chiyo’s work offers a distinct and personal perspective on the haiku form, making her a crucial figure in the development of Japanese poetry.

Kaga no Chiyo’s influence on the haiku tradition is lasting, and her work continues to inspire poets and readers around the world. Through her poetry, Chiyo reminds us of the beauty in the fleeting moments of life and the spiritual connection that binds us to nature. Her contributions to Japanese poetry, particularly in the haiku tradition, will undoubtedly endure for generations to come.