The villanelle, one of the most recognizable and structured forms in poetry, has captivated poets and readers for centuries with its intricate rhyme scheme, refrains, and haunting rhythms. This article will explore the history and origins of the villanelle, delving into its creator, development over time, and notable poets who have contributed to its evolution. We will also explore the structure of the villanelle itself, its characteristics, and its impact on contemporary poetry.

The Origins of the Villanelle

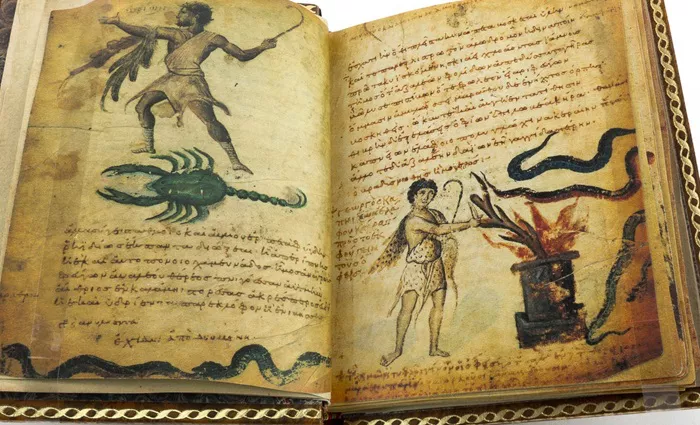

The origins of the villanelle are somewhat murky, but it is generally believed that the form originated in France during the late 16th century. The term “villanelle” itself comes from the French word “villanelle,” which initially referred to an Italian pastoral song or a rustic poem. The word was associated with rural, simple themes, and was often used to depict nature or rural life, a reflection of the form’s early themes. However, the true development of the form as we know it today is largely attributed to Italian and French poets.

The earliest known examples of the villanelle were influenced by Italian verse forms, but it was French poets who began to experiment with the fixed, repeated structure that would later define the villanelle. One of the first poets known to write a villanelle in its recognizable modern form was Joachim du Bellay, a French Renaissance poet, although it was his contemporary, Pierre de Ronsard, who perfected and popularized the structure.

The Structure of the Villanelle

A villanelle consists of 19 lines arranged in six stanzas: five tercets (three-line stanzas) and a final quatrain (four-line stanza). The key feature of the villanelle is its unique rhyme scheme and the use of refrains.

Rhyme scheme: The rhyme scheme of a villanelle is typically ABA for the tercets, and the quatrain (the final stanza) follows the pattern ABAA. This results in a repetition of the first and third lines of the first tercet, which are alternated throughout the poem as refrains. These repeated lines are crucial to the villanelle’s emotional power and give the poem a cyclical, almost hypnotic rhythm.

Refrains: The first line of the poem is repeated as the last line of the second and fourth tercets, while the third line is repeated as the last line of the third and fifth tercets. The final quatrain then brings both refrains together in the last two lines.

This repetition creates a sense of obsession, a continual return to key ideas or emotions, making the villanelle an effective form for exploring themes of love, loss, regret, or the passage of time. The repetition also heightens the emotional intensity, as the refrains often take on new layers of meaning as the poem unfolds.

Who Created the Villanelle?

While the origins of the villanelle as a distinct poetic form are traced back to 16th-century France, it is difficult to credit a single poet with “creating” the form. Rather, the villanelle evolved over time, shaped by a number of poets who contributed to its structure and use. However, Joachim du Bellay and Pierre de Ronsard are frequently cited as key figures in the development of the villanelle.

Joachim du Bellay (1522-1560) is often associated with the early use of the villanelle form, although his work did not strictly adhere to the modern structure. Du Bellay was one of the major figures of the French Renaissance and a member of the Pléiade, a group of poets who sought to enrich the French language by adopting and adapting classical models of poetry. Du Bellay’s work, such as his collection Les Regrets, shows his interest in experimenting with form, and it is likely that his exploration of traditional Italian and French poetic forms contributed to the development of the villanelle.

Pierre de Ronsard (1524-1585), another member of the Pléiade, is more directly connected to the development of the villanelle as it is recognized today. Ronsard was known for his mastery of poetic forms and for his ability to innovate within traditional structures. He refined the villanelle by introducing the use of refrains in a more structured and consistent manner, and his influence on the form cannot be overstated.

Though du Bellay and Ronsard played pivotal roles in the early use of the villanelle, it was French poets in the 19th century, particularly Gérard de Nerval and Paul Verlaine, who fully embraced and popularized the form in their works, further solidifying its place in the canon of European poetry.

The Villanelle’s Popularity and Use in the 19th Century

The villanelle’s resurgence in the 19th century marked a period of heightened interest in formal poetic structures and experiments with repetition. The fixed, cyclical nature of the form appealed to Romantic poets, who sought to explore the emotional resonance of repeated ideas. In France, poets such as Gérard de Nerval and Paul Verlaine adapted the villanelle to their own artistic needs.

Nerval, known for his melancholic and surreal poetry, used the villanelle to express feelings of longing, despair, and the passage of time. One of his most famous villanelles is “El Desdichado,” which beautifully illustrates how the form can be used to express intense emotion through the repetition of key phrases.

Verlaine, another influential poet of the period, also experimented with the villanelle. His poem “La Villanelle des Petits Enfants,” demonstrates how the form can capture both the playful and poignant aspects of life, shifting between light-heartedness and deeper emotional undertones.

The 19th century also saw the villanelle becoming a favored form among English poets. Edgar Allan Poe, known for his dark and gothic themes, was one of the first to bring the villanelle to English-speaking audiences. His poem “The Raven“—though not strictly a villanelle—shares the form’s obsessive repetition of key lines, and it likely influenced other poets to experiment with the form.

The Villanelle in Modern Poetry

Despite its somewhat traditional structure, the villanelle has continued to evolve and remain relevant in contemporary poetry. Modern poets have embraced the form for its unique ability to convey complex emotions while adhering to a strict structure. The work of poets such as Dylan Thomas, W. H. Auden, and Elizabeth Bishop illustrates how the villanelle can be used to explore a wide range of themes, from existentialism to the exploration of personal loss.

Perhaps the most famous modern example of a villanelle is Dylan Thomas’s “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night.” Written in the early 1950s, this villanelle is a powerful meditation on death, resistance, and defiance. The repeated refrains—“Do not go gentle into that good night” and “Rage, rage against the dying of the light”—take on a deeply emotional resonance as the poem progresses, emphasizing the speaker’s urgent plea for resistance against the inevitable.

In addition to Thomas, other poets like W. H. Auden and Elizabeth Bishop have used the villanelle to engage with themes of loss, memory, and the passage of time. Auden’s “The More Loving One” and Bishop’s “One Art” both exemplify the form’s versatility, showing how it can be adapted to explore different emotional landscapes while maintaining its inherent structure.

Conclusion

The villanelle has a rich and complex history that spans centuries and countries, from its rustic Italian origins to its refinement in France and its eventual adoption in English and other languages. While it is difficult to pinpoint a single creator of the villanelle, poets like Joachim du Bellay, Pierre de Ronsard, and later Gérard de Nerval, Paul Verlaine, and Dylan Thomas have all played important roles in shaping the form into what it is today.

The villanelle’s distinct structure—characterized by its use of refrains and its rigid rhyme scheme—has made it a powerful vehicle for expressing intense emotion, obsession, and the passage of time. Today, the villanelle continues to be used by contemporary poets, who appreciate the form’s ability to evoke deep feelings and thoughts while adhering to a fixed structure. As such, the villanelle stands as a testament to the enduring power of structured verse and the creativity of the poets who continue to adapt and expand its possibilities.