Emmett Williams, born in 1925, was a pioneering figure in 20th-century American poetry. His work spanned across a diverse range of styles, from visual poetry and concrete poetry to more traditional forms of lyricism. His influence in the American poetry landscape is profound, not only because of his distinctive approach to language and form but also because of his role in the broader experimental movement of the 20th century. As we explore the life and work of Emmett Williams, we must consider his contributions in the context of American poetry at large and compare his work with that of his contemporaries. This article delves into the life of Emmett Williams, his poetic innovations, and his place within the broader field of 20th-century American poetry.

The Early Life of Emmett Williams

Emmett Williams was born in the small town of Greenville, South Carolina, in 1925. He came from a background that was both rooted in the Southern United States and shaped by the greater cultural currents of mid-20th-century America. Williams’ early life was marked by his education, which led him to pursue his studies at the University of South Carolina, where he developed a foundation in the classical literary traditions. However, his intellectual journey was not confined to academic pursuits. After moving to New York in the 1950s, he began to immerse himself in the dynamic and evolving poetry scene that was taking shape across the United States.

The 20th century saw the rise of a new generation of poets who sought to push the boundaries of poetic form, language, and meaning. Emmett Williams, alongside many of his peers, was part of this movement, embracing an experimental and avant-garde approach to poetry. This was a time of great cultural upheaval in America, with the emergence of Abstract Expressionism in the visual arts, the rise of jazz and popular music, and the expanding influence of European modernism on American culture. Williams’ work reflects this period of transformation and innovation.

The Emergence of Williams as a 20th Century American Poet

In the 1950s and 1960s, Emmett Williams began to make his mark in the American poetry scene. This period saw the rise of the New York School of Poets, including figures such as John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, and Kenneth Koch. Williams, though not directly associated with the New York School, shared many of their experimental sensibilities. His works often subverted conventional poetic forms, engaging with themes of language, perception, and identity. Williams’ poetry was distinct in its attention to the visual and spatial elements of language, which was a precursor to the concrete poetry movement.

Concrete poetry, which involves the use of visual elements to enhance or alter the meaning of words, became one of Williams’ primary modes of expression. He was deeply influenced by the European avant-garde poets, such as Guillaume Apollinaire and the Italian Futurists, who had explored similar visual aspects in their work. In this context, Williams’ poetry can be understood as part of a broader global movement that sought to transcend the limitations of traditional poetic forms and engage with poetry as a form of artistic expression that could not be confined to the written word alone.

Williams’ Poetic Style: Visual and Concrete Poetry

The hallmark of Emmett Williams’ poetry is his use of visual elements to create meaning. His works often incorporate abstract shapes, symbols, and layouts on the page that draw attention to the physical form of the text itself. These visual elements disrupt the linear, word-based conventions of poetry, challenging readers to engage with the text in new and dynamic ways. Williams was particularly adept at using the page as a canvas, where the arrangement of words became as important as the words themselves.

One of Williams’ most famous works in this genre is his poem “The Reader” (1967), which exemplifies his exploration of concrete poetry. In this work, the words are arranged in a way that reflects the shape of the object being described. The poem’s structure mimics the act of reading, where the text’s visual form is interwoven with its content. This blurring of boundaries between form and content is a central feature of Williams’ poetic approach.

Williams’ exploration of concrete poetry was not limited to individual poems. He also collaborated with other poets and artists to produce works that pushed the limits of what poetry could be. In his collection “Poetry in the Shape of a Rose” (1966), Williams collaborated with visual artists to create a book that was as much a work of visual art as it was a poetic collection. These collaborations exemplified his belief that poetry could be an interdisciplinary art form, merging visual, linguistic, and conceptual elements.

Emmett Williams and the Fluxus Movement

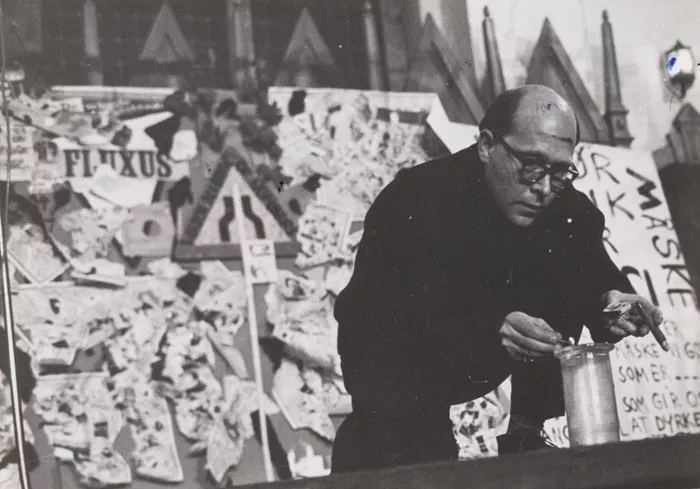

Another significant aspect of Emmett Williams’ career was his involvement with the Fluxus movement, an international collective of artists and poets who sought to challenge the conventional boundaries between different artistic mediums. Fluxus, which emerged in the early 1960s, was rooted in the idea that art should be accessible, experimental, and performative. Emmett Williams, as both a poet and a visual artist, played a key role in the movement, using poetry as a medium for performance and collaboration.

Fluxus artists rejected the formalities of the art world and sought to create work that was both democratic and participatory. Williams’ work with Fluxus artists, such as George Maciunas, Nam June Paik, and Yoko Ono, helped redefine the nature of poetry in the 20th century. In Fluxus, poetry was not just something to be read—it was something to be experienced. Williams participated in Fluxus events that combined poetry, performance, and visual art, reflecting the movement’s interdisciplinary ethos. His poems, often marked by their wit and conceptual playfulness, were perfectly aligned with the Fluxus spirit.

The Legacy of Emmett Williams in American Poetry

Emmett Williams’ contributions to 20th-century American poetry cannot be understated. As a poet, he was instrumental in shifting the focus of American poetry from traditional forms of lyricism to more experimental and visual approaches. His work is often compared to that of other American poets of the time who were similarly engaged with the experimental turn in poetry. For example, poets like John Ashbery and Frank O’Hara, who were part of the New York School, were also known for their fragmented, collage-like poetry. However, Williams distinguished himself by focusing more explicitly on the visuality of language, whereas Ashbery and O’Hara often explored the internal complexities of subjectivity and perception.

The 20th-century American poet also found himself in dialogue with other experimental poets outside of the United States. In Europe, poets like Eugen Gomringer and Hansjörg Mayer were also embracing concrete poetry and other avant-garde forms. Williams’ work in visual poetry, particularly his collaborations with visual artists, places him within this broader international movement, further cementing his role as a global figure in 20th-century poetry.

In the context of American poetry, Williams is often regarded as one of the more innovative and boundary-pushing poets of his generation. While many American poets of the 20th century, such as Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens, and Sylvia Plath, adhered to more traditional forms of poetry, Williams stood apart by using visual techniques and performance to challenge the very nature of poetry itself. His work helped pave the way for later poets and artists who continue to experiment with language, form, and media.

Emmett Williams: A Comparative Perspective

In comparison to other poets of the same period, Williams’ work can be seen as part of a larger wave of experimental poetry that emerged in the 20th century. However, his focus on the visual and performative aspects of poetry sets him apart from his contemporaries. For instance, John Cage, who was also associated with the Fluxus movement, approached sound and silence as crucial elements of poetic composition. While Williams was concerned with the visual aspects of poetry, Cage’s work engaged more deeply with sound and auditory experiences.

Similarly, poets like William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, key figures in the Beat Generation, were also experimenting with language and form. However, their work was often more concerned with social issues and the exploration of consciousness, while Williams’ work focused more on the intrinsic properties of language itself. In this sense, Williams can be seen as a poet who was less concerned with content in the traditional sense and more interested in how language could be manipulated and visually presented.

Conclusion

Emmett Williams’ influence on 20th-century American poetry and the wider field of visual poetry remains significant. His experiments with concrete poetry, his role in the Fluxus movement, and his collaborations with artists and poets have left a lasting mark on the world of poetry. As an American poet, Williams was part of a larger movement of experimental writers who sought to push the boundaries of what poetry could be. His work remains a testament to the power of innovation and artistic exploration in shaping the landscape of American poetry.

In the 21st century, Emmett Williams’ legacy continues to inspire poets and artists alike. His belief in the fluidity of language and the potential for poetry to transcend its traditional boundaries remains a central theme for contemporary writers. As we look back on his life and work, we see a poet who not only contributed to the evolution of American poetry but also helped redefine what it meant to be a poet in the 20th century.

Williams’ work is an essential part of the conversation about 20th-century American poetry, and his contributions serve as a reminder that poetry is an ever-evolving art form that is capable of breaking free from the constraints of the past. Through his experimentation with form, language, and visual art, Emmett Williams helped shape the direction of American poetry and left a legacy that will continue to influence future generations of poets.