The 20th century was a time of profound upheaval, both politically and artistically. Across Europe, artists grappled with the consequences of industrialization, the trauma of world wars, and the disillusionment of modern life. In the realm of German poetry, few figures exemplify the spirit of radical experimentation and existential inquiry better than Hugo Ball. As a central figure in the Dada movement, Ball’s contributions to German poetry were both foundational and revolutionary.

While many poets of the time sought solace in tradition or structure, Hugo Ball shattered conventions. His poetry was not only a reflection of personal angst but also a critique of language, society, and meaning itself. In this article, we explore the life, works, and influence of Hugo Ball, the 20th Century German poet who reshaped modern literature and forever altered the trajectory of German poetry.

Early Life and Intellectual Formation

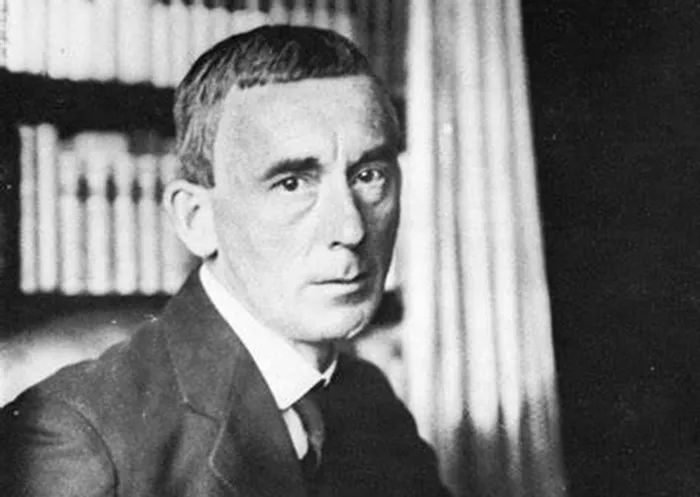

Born on February 22, 1886, in Pirmasens, Germany, Hugo Ball grew up in a period marked by political conservatism and cultural rigidity. He studied philosophy and literature in Munich and Heidelberg, immersing himself in the ideas of Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, and early German Romanticism. These intellectual foundations would later feed into his artistic revolt against rationalism and nationalism.

Ball initially aspired to become a philosopher or dramatist. However, the outbreak of World War I and the rise of militaristic nationalism disillusioned him. As a young German poet, Ball felt alienated from the mainstream literary currents that glorified war and tradition. His discontent found expression not in the quiet solitude of verse but in radical performance, absurdity, and revolt.

The Dada Movement and the Birth of Anti-Poetry

In 1916, Ball co-founded the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, Switzerland. Zurich was neutral territory during World War I, and it became a haven for exiled artists and intellectuals. It was here that Ball became a central figure in the Dada movement, which rejected traditional aesthetics, logic, and cultural norms.

Ball’s poetry during this period defies conventional categorization. He coined the term “sound poetry” to describe his abstract vocal compositions, which consisted of non-lexical syllables, chants, and guttural expressions. One of his most famous performances was the poem Karawane, in which nonsensical syllables evoke rhythms and emotions beyond logical comprehension. The poem begins:

“jolifanto bambla ô falli bambla

grossiga m’pfa habla horem…”

This work typifies Hugo Ball’s role as a 20th Century German poet who sought to liberate language from its association with political propaganda and rational meaning. He believed that traditional language had been corrupted by war and bureaucracy, and that poetry needed to be purified through nonsense and sound.

Poetic Philosophy and Aesthetic Vision

Ball’s views on poetry were deeply philosophical. In his Dada Manifesto of 1916, he proclaimed: “I shall be reading poems that are meant to dispense with conventional language, no less, and to have done with it.” For Ball, words were not just vehicles of meaning—they were spiritual entities.

This attitude marked a break with earlier German poets, such as Rainer Maria Rilke, whose lyrical style emphasized introspection and spiritual longing within a recognizable linguistic structure. While Rilke used language to transcend, Ball attempted to destroy and rebuild it from its phonetic roots.

Hugo Ball’s poetry is not always easy to digest. It resists interpretation. But that is its strength. As a 20th Century German poet, Ball forced readers and listeners to confront the arbitrariness of language. He asked: if meaning can be created from nonsense, what then is the value of sense?

Ball and His Contemporaries

To fully understand Hugo Ball’s place in 20th-century German poetry, it is helpful to compare him with his contemporaries. The early 20th century was a dynamic period for German literature, producing a wide spectrum of poetic voices.

Rainer Maria Rilke

Rilke, born in 1875, was about a decade older than Ball. His work, particularly the Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus, explored existential themes with rich symbolism and musical language. Unlike Ball, Rilke embraced the traditions of lyric poetry, believing in the possibility of beauty and transcendence through carefully crafted verse.

Where Ball deconstructed language, Rilke refined it. Both poets, however, were deeply spiritual. Ball’s later writings, such as his religious diaries and the biography of Christian mystic Simon Stylites, reflect a turn towards a more traditional but introspective Christian spirituality.

Georg Trakl

Trakl, another contemporary, was an Austrian poet associated with Expressionism. His poetry, such as Grodek, captures the horror and desolation of war through surreal and haunting imagery. Like Ball, Trakl rejected realism, but where Ball used absurdity, Trakl used mysticism and decay. Trakl’s death in 1914, early in World War I, cut short a promising career, but his work had a lasting influence on German poetry.

Bertolt Brecht

Brecht, born in 1898, emerged slightly later but became one of the most influential German poets and playwrights of the 20th century. His political poems, with their accessible language and didactic tone, contrast sharply with Ball’s esoteric sound poetry. While Brecht sought to engage the masses through clarity and ideology, Ball aimed for a spiritual and metaphysical cleansing of language.

These comparisons show that German poetry in the 20th century was not a monolith. It ranged from the lyrical (Rilke) to the surreal (Trakl) to the political (Brecht) to the avant-garde (Ball). Hugo Ball’s contribution stands out for its radical formal innovation and philosophical depth.

The Crisis of Meaning in Modern German Poetry

Hugo Ball’s experiments were not isolated acts of rebellion. They reflected a larger crisis in European culture, particularly in German poetry. The devastation of World War I shattered many of the ideals that had shaped 19th-century thought—progress, rationalism, nationalism.

In this context, Ball’s poetry can be read as a form of protest. By tearing apart syntax, grammar, and semantics, he was symbolically tearing apart the ideologies that had led Europe into chaos. His rejection of traditional verse forms was also a rejection of the bourgeois values they represented.

German poetry in the early 20th century became a site of struggle over meaning itself. While some poets tried to recover meaning through religious or emotional depth, Ball sought to reveal its instability. This tension between restoration and deconstruction continues to shape German literature today.

Legacy and Later Years

After his Dada period, Hugo Ball distanced himself from the movement, which he felt had become too nihilistic. In his later years, he turned to religious contemplation, converting to Catholicism and writing theological essays. His biography of Saint Hermann-Joseph and his mystical reflections in Flight Out of Time show a different side of the poet—a seeker of inner truth.

Yet even in his spiritual writings, the influence of his poetic experimentation remains. Ball never lost his belief in the sacred power of language, even if that power was elusive and fragile. He died in 1927, but his ideas continued to influence later generations of poets, sound artists, and performance theorists.

Influence on Later Movements and Global Literature

Hugo Ball’s contributions extended beyond German borders. His experiments with sound poetry influenced the Beat poets in America, as well as performance artists and experimental musicians throughout the 20th century. Writers like Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, and even musicians like Laurie Anderson have cited Dada as an inspiration.

Within German poetry, his legacy can be seen in the works of Hans Arp (who collaborated with Ball), Kurt Schwitters, and later experimental writers of the post-war avant-garde, including those associated with the Wiener Gruppe and concrete poetry.

His impact also resonates in modern performance art and spoken word poetry. Ball’s insistence that poetry is not merely text on a page, but an event in space and time, has revolutionized how poets think about the medium itself.

Conclusion

Hugo Ball remains one of the most original and provocative voices in 20th-century German poetry. His works challenge readers to question not only what poetry is but what language itself can do. In a century marked by ideological conflict and cultural fragmentation, Ball offered a vision of poetry that was both radical and redemptive.

As a German poet, he stands apart for his bold experimentation and his spiritual introspection. As a pioneer of Dada and a seeker of mystical truth, he captured the contradictions of his age. His poetry, often dismissed as mere absurdity, is in fact a profound meditation on the collapse—and potential renewal—of meaning.

In understanding Hugo Ball, we gain a deeper insight into the nature of German poetry and the wider currents of 20th-century thought. His legacy continues to inspire poets, artists, and thinkers who believe that language, however fractured, still holds the power to awaken the soul.