Georg Trakl stands as one of the most important figures in 20th Century German poetry. Known for his dark imagery, haunting symbols, and profound introspection, Trakl’s work exemplifies the transition from late Romanticism to early Expressionism. His poetry is filled with silence, decay, and a mystical vision of human suffering. His influence on modern German poets and writers is enduring, as is his unique place within the literary landscape of his time.

Trakl’s poetic voice is both individual and universal. His themes of death, isolation, and redemption reflect both personal trauma and the broader turmoil of his era. To understand Georg Trakl is to understand the spirit of early 20th Century German poetry, a period marked by war, fragmentation, and the search for spiritual meaning.

This article explores Trakl’s life, themes, style, and literary context. It will also compare Trakl to other German poets of the 20th century, such as Rainer Maria Rilke and Gottfried Benn, highlighting both commonalities and distinctions.

Life and Historical Context

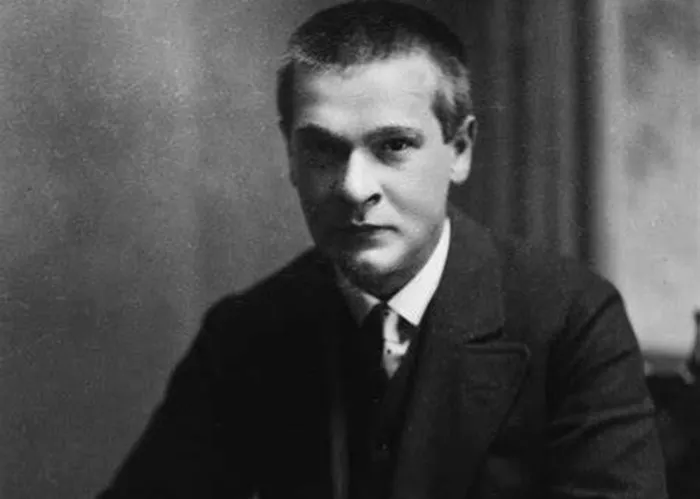

Georg Trakl was born in Salzburg, Austria-Hungary, on February 3, 1887. Though Austrian by nationality, he is typically classified among German poets due to his use of the German language and his literary associations. He studied pharmacy in Vienna and served as a medical officer during World War I, experiences that would deeply shape his poetic vision.

Trakl’s life was marked by psychological instability, drug addiction, and a constant sense of despair. His relationship with his sister Grete, whom he idolized, has been the subject of much speculation and psychoanalytic interpretation. Trakl died in 1914 at the age of 27, likely by suicide, during the early months of the war.

The early 20th century was a time of great upheaval in Europe. The old order was collapsing. New artistic movements such as Expressionism and Symbolism challenged traditional forms. Trakl’s poetry reflects this cultural moment. He was both a product of his time and a prophet of the horrors to come.

Themes in Trakl’s Poetry

1. Death and Decay

Death is the central motif in Trakl’s work. It is not merely an end, but a process of dissolution and transformation. His landscapes are filled with autumn, evening, and fading light—symbols of transition and entropy. In poems like “Grodek,” written shortly before his death, Trakl depicts the horror of war as a descent into silence and ruin.

“At evening the autumn woods resound

With deadly weapons, the golden plains

And blue lakes, over which the sun

Rolls in mournful majesty, are filled

With dark lamentation.”

(from “Grodek”)

Here, the natural world reflects the internal collapse of the human spirit. Trakl’s imagery is apocalyptic, yet strangely beautiful. His vision of death is spiritual as well as physical.

2. Silence and Stillness

Silence in Trakl’s poetry is not emptiness. It is presence. It is the echo of trauma, the space left after meaning has collapsed. The poet does not attempt to fill silence with speech. He listens to it. He dwells in it.

Silence is often connected to evening, to winter, and to dying. In many poems, characters fall silent, or disappear into a quiet landscape. Silence is also linked to Trakl’s mysticism. It is the silence of God, or of the divine absence.

3. Spiritual and Mystical Language

Trakl’s poetry often hints at a lost or unreachable sacred order. Religious language appears in his work, but it is fragmented and ambiguous. Words like “grace,” “sin,” “angels,” and “redemption” appear, but they are disconnected from any clear theological system.

In this way, Trakl’s mysticism is modern. It reflects a crisis of faith. His poems yearn for transcendence, but find only shadows. This spiritual tension is one of the reasons why Trakl’s work resonates so deeply with readers of modern and contemporary German poetry.

4. Personal Suffering

Trakl’s poems are often autobiographical in tone, though not in content. They express deep sorrow, alienation, and inner division. Critics have read his poetry through the lens of his mental illness, his addiction to drugs, and his possible incestuous feelings for his sister. Whether one accepts these readings or not, it is clear that Trakl’s poetry is a cry of pain.

His suffering is not self-indulgent, however. It is transformed through poetic form into something universal. The personal becomes archetypal. Trakl’s pain becomes the world’s pain.

Language and Style

Symbolism and Imagery

Trakl’s poetry is dense with symbols. These symbols are not static or fixed. They shift and shimmer. Common motifs include twilight, blood, snow, crows, wolves, and dead trees. These images create a dreamlike atmosphere, one in which meaning is both suggested and withheld.

Colors are especially important. Blue and gold appear frequently. Blue often represents melancholy, transcendence, or infinity. Gold may suggest beauty or corruption. Color in Trakl is always emotional.

Syntax and Structure

Trakl’s language is deceptively simple. He uses short clauses, often in the present tense. But the simplicity is deceptive. His grammar is fractured. His lines are elliptical. Sentences trail off. Logic dissolves.

This disintegration of syntax reflects the disintegration of the world. Form mirrors content. The very structure of language in Trakl’s poetry expresses what cannot be said.

Musicality and Rhythm

Trakl’s poetry has a hypnotic rhythm. He often uses repetition and parallel structure. His poems have a musical quality, even when they are somber. This music is part of the emotional power of his work. It carries the reader into a world that is at once beautiful and terrifying.

Georg Trakl and His Contemporaries

Rainer Maria Rilke

Rilke and Trakl are often mentioned together as leading voices in German poetry of the early 20th century. Both were influenced by Symbolism and shared a mystical sensibility. But their temperaments were different.

Rilke’s poetry often affirms life. Even when he writes about death, he sees it as part of a cosmic order. His “Duino Elegies” express a vision of transformation and angelic insight.

Trakl, by contrast, offers no such consolation. His angels are silent or absent. His vision is darker, more fractured. Where Rilke seeks meaning, Trakl reveals its collapse.

Gottfried Benn

Benn was a contemporary of Trakl and another major figure in early 20th Century German poetry. Benn was also a doctor, and his early poetry, like Trakl’s, is filled with images of decay and disease.

However, Benn’s approach is more clinical, more ironic. He distances himself from emotion. Trakl is deeply emotional, even romantic. While both poets deal with death and the body, Trakl does so with a mystical intensity that sets him apart.

Expressionist Poets

Trakl is often grouped with the Expressionists, though his work also shows traits of late Romanticism and Symbolism. Expressionist poets such as Georg Heym and Else Lasker-Schüler also explored themes of urban anxiety, death, and spiritual crisis.

What distinguishes Trakl is his inwardness. His poems are not about the city, but about the soul. His vision is hermetic. He does not engage in social critique, but in metaphysical exploration.

Influence and Legacy

Trakl’s influence can be seen in later German poets, such as Paul Celan and Ingeborg Bachmann. Celan in particular drew on Trakl’s dense imagery and spiritual intensity. Both poets explore trauma, silence, and the limits of language.

In post-war German poetry, Trakl came to represent a kind of prophetic voice. His poems seemed to anticipate the horrors of the 20th century. His breakdown was seen as symbolic of a larger cultural collapse.

Trakl’s work has also influenced composers (like Anton Webern), visual artists, and philosophers. Heidegger wrote about Trakl’s vision of language and being. The wide range of Trakl’s influence is a testament to the depth and richness of his work.

Conclusion

Georg Trakl was a unique voice in 20th Century German poetry. His haunting imagery, spiritual yearning, and psychological depth mark him as one of the most important German poets of his time. His work stands at the intersection of Romanticism, Symbolism, and Expressionism, yet it transcends any single category.

In comparing Trakl to poets like Rilke and Benn, we see both shared concerns and profound differences. Trakl’s singular vision—bleak, beautiful, and deeply human—continues to move readers today.

His poetry reminds us of the fragility of meaning, the presence of silence, and the possibility of grace even in ruin. For all his darkness, Trakl was a seeker of light. His legacy is not one of despair, but of poetic courage.

In the landscape of German poetry, Georg Trakl is a solitary figure. But his solitude speaks to us. His voice, quiet and sorrowful, continues to echo through the corridors of 20th and 21st century literature.