The 20th century was a transformative period for British poetry. During this time, the conventions of Victorian verse gave way to a new range of voices, styles, and concerns. Amid the cacophony of experimentation, one figure stands out for his precision, musicality, and unique philosophical vision: Basil Bunting. As a 20th Century British poet, Bunting’s work represents a compelling synthesis of modernist technique and regional sensitivity. Despite being less well-known than contemporaries such as T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, or Dylan Thomas, Bunting remains a central figure in understanding the evolution of British poetry in the modern era.

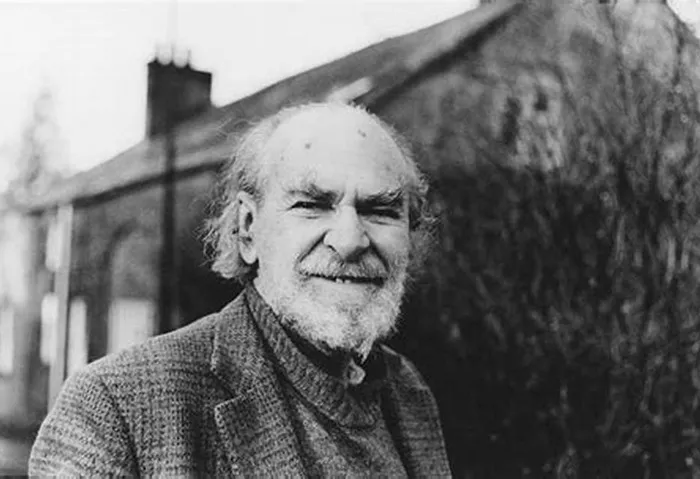

Basil Bunting

Basil Bunting was born in 1900 in Northumberland, England. His Quaker upbringing and early exposure to the landscapes of the North East would later shape both the moral tone and setting of his poetry. Bunting’s early interest in music and languages also played a significant role in his poetic development. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Bunting did not attend university. Instead, he pursued independent intellectual exploration, which included travels through Europe and the Middle East. This cosmopolitan experience broadened his aesthetic horizon and introduced him to diverse poetic traditions.

Among his early influences were the works of Ezra Pound and the modernist movement more broadly. Pound, in particular, was a defining figure in Bunting’s life. The two poets met in the 1920s, and Bunting became an ardent disciple of Pound’s poetic philosophy, especially the principles of Imagism and Vorticism. This mentorship influenced Bunting’s emphasis on the musicality of verse, clarity of image, and condensation of language.

Modernist Style and Poetic Philosophy

As a 20th Century British poet, Bunting’s alignment with Modernism was both aesthetic and philosophical. He believed that poetry should be heard rather than merely read. For Bunting, the sound of a poem was its lifeblood. This belief underpinned his most famous assertion: “Poetry is sound.” Consequently, his poems are meant to be performed aloud, where rhythm, cadence, and tonal inflection become part of their meaning.

This approach aligns him with other modernist poets such as T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. However, where Eliot often employed a formal, intellectual tone and allusion-heavy diction, Bunting’s work remained grounded in sensory experience and personal memory. His syntax is often elliptical, his lines tight and compressed. This minimalism invites careful listening and repeated reading.

In comparison to W.H. Auden, another major 20th Century British poet, Bunting was less concerned with political commentary and more focused on the internal music of language. Auden’s poetry frequently grappled with the crises of the age—fascism, war, the threat of totalitarianism. Bunting, by contrast, turned inward, emphasizing the metaphysical over the ideological.

Key Works: Briggflatts and Beyond

Bunting’s magnum opus, Briggflatts (1966), is widely regarded as one of the great achievements in 20th Century British poetry. Written in his sixties after a long period of poetic silence, Briggflatts is an autobiographical poem that weaves together personal history, regional identity, and philosophical reflection.

Set in the dialect and landscape of Northumberland, the poem is both a love letter to the English countryside and a meditation on the passage of time. Structured as a five-part musical composition, Briggflatts explores themes of love, loss, and the transience of life. Its language is economical but lush, its rhythms intricate and carefully orchestrated. The influence of music—especially classical composition—is deeply embedded in the poem’s structure.

In the context of British poetry, Briggflatts stands apart for its formal innovation and emotional depth. Unlike the more programmatic verse of Auden or the mythic ambition of Ted Hughes, Bunting’s poem carves out a space that is intensely personal yet universally resonant.

Relationship with Other Poets and Traditions

Bunting’s career was closely linked to that of Ezra Pound. He worked for Pound at the Rapallo radio station and later defended Pound during his incarceration. Bunting’s admiration for Pound was deep but not uncritical. He adopted many of Pound’s techniques but applied them to his own local and personal contexts.

In contrast to Dylan Thomas—a fellow British poet known for his lush, lyrical style—Bunting’s verse is more austere and restrained. Thomas reveled in the musicality of language, but his work often bordered on the baroque. Bunting’s music is subtler, more internal. Yet both poets shared an emphasis on sound and the emotive power of spoken language.

Bunting was also influenced by Persian poetry, particularly the work of Ferdowsi and Hafez. His translations and adaptations of Persian verse reveal a deep respect for non-Western literary traditions. These interests broaden the scope of British poetry, situating it within a more global context. This cosmopolitanism aligns him with poets like Kathleen Raine and David Jones, who also looked beyond the Anglo-American canon.

Themes and Concerns

Bunting’s poetry frequently deals with time, memory, and mortality. In Briggflatts, he reflects on lost love and the inevitability of death. These themes are universal, yet Bunting approaches them through a deeply personal lens. The landscapes of Northumberland are not mere backdrops—they are active participants in the emotional narrative.

Another persistent theme in Bunting’s work is the tension between permanence and change. He often contrasts the solidity of nature—the rocks, the rivers, the hills—with the fleeting nature of human experience. This contrast lends his poetry a meditative, almost spiritual quality. His Quaker background may account for some of this introspective depth.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Bunting largely eschewed political themes. While poets like Auden, Spender, and MacNeice engaged directly with the political turmoil of the 20th century, Bunting focused on more timeless concerns. This does not mean his work is apolitical; rather, its politics are embedded in its aesthetics. The act of listening, of attending closely to sound and sense, becomes a form of resistance against the noise of modern life.

Later Years and Legacy

After the publication of Briggflatts, Bunting experienced a late renaissance. He was celebrated by younger poets, especially those involved in the British Poetry Revival of the 1960s and 70s. Figures such as Tom Pickard and Jeremy Prynne saw Bunting as a bridge between the modernist tradition and contemporary experimentalism.

Despite this recognition, Bunting remained something of an outsider. He never sought fame and often distrusted literary institutions. Yet his influence has endured. Today, Bunting is studied not only as a historical figure but as a living presence in British poetry. His work continues to inspire poets who value precision, musicality, and philosophical depth.

Comparison with Contemporary British Poets

In assessing Bunting’s place among 20th Century British poets, it is helpful to consider his contemporaries. T.S. Eliot, with The Waste Land and Four Quartets, defined the high-modernist aesthetic. Auden, with his public voice and moral engagement, captured the spirit of a generation. Dylan Thomas, with his lush imagery and orality, redefined the lyrical tradition.

Bunting stands apart. He was neither a public intellectual like Eliot nor a populist bard like Thomas. He was a craftsman, devoted to the line, the syllable, the sound. His work lacks the broad social commentary of Auden but offers instead a purity of focus—a poetry of distilled essence. In this sense, Bunting may be closer to poets like David Jones or Geoffrey Hill, whose works also demand careful listening and deep reflection.

Conclusion

Basil Bunting is a unique voice in the landscape of 20th Century British poetry. As a British poet, he contributed a body of work that is both regional and universal, musical and philosophical. His commitment to sound, form, and meaning sets him apart from his contemporaries. While he may never have achieved the fame of Eliot or Auden, his influence is no less profound. Bunting reminds us that poetry is not just a vehicle for ideas but a mode of experience—a way of seeing and hearing the world anew. His legacy endures in the continued resonance of Briggflatts and in the work of those poets who value the art of attentive listening.

In understanding Bunting, we come to understand a quieter, subtler strand of British poetry—one that sings not in the marketplace, but in the hills and rivers of a remembered Northumberland.