Welcome to Poem of the Day – A cool fall night by Matsuo Basho.

Matsuo Bashō, one of the most revered figures in Japanese literature, is best known for his mastery of haiku, a form of poetry that captures moments of deep reflection, often using nature as a vehicle for emotional and philosophical exploration. His works are rooted in the aesthetics of simplicity, evanescence, and the profound connection between human experience and the natural world.

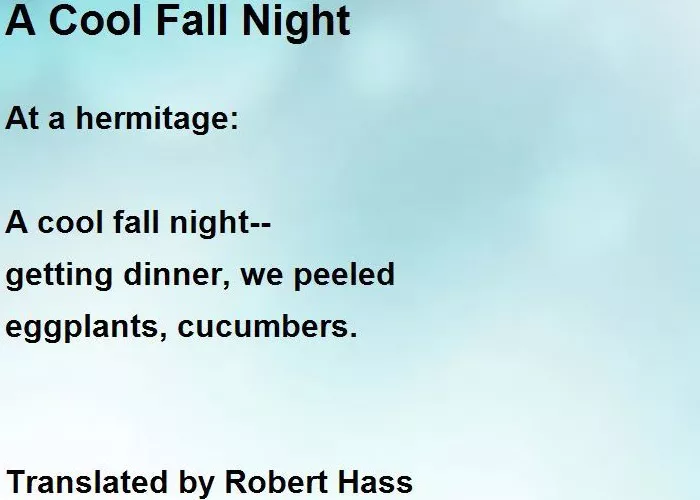

A Cool Fall Night Poem

At a hermitage:

A cool fall night;

getting dinner, we peeled

eggplants, cucumbers.

A Cool Fall Night Poem Explanation

Though this particular haiku evokes the transient beauty of spring, Bashō’s approach to nature and time remains consistent throughout his work. His poetry often dwells on the fleeting nature of existence, the delicate passage of time, and the transient beauty of moments. Among his many celebrated haikus, one of the most vivid and atmospheric. This particular haiku is a reflection on both the impermanence of life and the quiet power of nature’s presence. Let us explore this work with a detailed analysis that uncovers Bashō’s intricate use of imagery, emotion, and philosophical underpinnings.

The Setting: A Cool Fall Night

The opening phrase, “On a cool fall night,” immediately sets the tone for the poem. Fall, or aki in Japanese, is a season that holds a special place in Japanese culture. It represents not only the change of seasons but also a deeper, existential reflection on the passage of time. The “cool” night evokes a sense of crispness in the air, as if the warmth of summer is gently giving way to the cold embrace of winter. Fall, particularly in the Japanese context, is associated with the mono no aware (物の哀れ) — the awareness of the impermanence of things and the bittersweet beauty of that transience. This awareness is perhaps the most defining feature of Bashō’s work.

A cool fall night is a sensory experience: the air, the quiet, the stillness that envelops everything. Bashō does not describe the fall night in great detail, but the simplicity of the phrase allows the reader to fill in the gaps with their own sensory experiences. The cool air contrasts with the warmth of the day, and the stillness of the night suggests a moment of introspection, a pause in time that invites reflection. By using just a few words to evoke this image, Bashō taps into the reader’s own memory of fall, creating a sense of shared experience.

The Cry of the Bird: A Sound in the Silence

The second line, a bird cries from the hills, introduces an auditory element that punctuates the otherwise still scene. The bird’s cry, which is both natural and primal, serves as a symbol of life’s enduring presence even in moments of solitude and silence. The bird itself may not be the focus of the haiku, but its cry is a crucial element that adds emotional depth to the scene.

In this haiku, the bird’s call could be interpreted as a metaphor for human longing or the cry of existence itself. It is a reminder that life continues on, even when enveloped in quiet. Just as the fall night is “cool,” the bird’s cry carries with it an emotional chill, a reminder of the inevitability of time passing. It is a sound that resonates not just through the physical landscape but also through the emotional landscape of the poet, and of the reader. The bird’s cry adds an existential layer to the poem, reflecting Bashō’s awareness of the impermanence of all life — a theme central to many of his works.

The Mist: The Transience of Sound and Life

Finally, the haiku ends with the poignant observation that the bird’s voice is “lost in the mist.” This closing line is perhaps the most haunting and philosophical part of the poem. The mist serves as a metaphor for the unknowable, the ephemeral, and the obscured. The bird’s cry, though heard for a moment, dissipates into the mist, swallowed by the vastness of the night. This imagery is a vivid representation of the Buddhist concept of mujo (無常), the impermanence of all things.

The mist itself is intangible, fleeting, and impossible to hold onto, much like the sounds of the bird’s cry. This image could also be interpreted as the inability of human emotions and experiences to ever truly be captured or preserved. The cry, although real in the moment, is rendered invisible and indistinguishable by the mist — an ultimate reminder of the transience of life itself. It is this loss of sound, this fading of life’s moments into the unknown, that captures the essence of Bashō’s philosophical approach. What is here one moment may be gone the next, and it is this fleetingness that lends life its beauty and poignancy.

The Emptiness Between the Words

In this haiku, Bashō’s minimalist approach to language enhances the impact of the poem. He says just enough to evoke a deep emotional response from the reader, but not so much as to over-explain the scene. This allows the haiku to resonate on a deeper level, where silence and absence carry as much weight as the words themselves. In a way, the missing moments, the things unsaid, are as important as the elements that Bashō chooses to describe.

Bashō’s use of simplicity in language, combined with the power of the natural world, creates a space where readers can project their own emotions and thoughts onto the poem. The bird’s cry, the mist, and the cool fall night all become symbols of life’s brief, fragile nature — and ultimately, of the human experience itself.

Conclusion

Matsuo Bashō’s haiku, On a cool fall night, a bird cries from the hills, its voice lost in the mist, captures the essence of his poetic philosophy — a contemplation of the fleeting and impermanent nature of existence. Through the use of sensory details, sound, and imagery, Bashō evokes a profound moment of stillness and reflection. The cool fall night, the cry of the bird, and the mist that absorbs its sound all come together to create an atmosphere of quiet transience, a perfect encapsulation of mono no aware — the sadness and beauty that arise from the awareness of the impermanence of life. In just a few lines, Bashō invites the reader to experience not only the moment itself but also the deeper, existential truth that lies beneath it. Through simplicity and nature, Bashō reminds us that life, like the bird’s cry, is both fleeting and precious.