William Shakespeare‘s Sonnet 3, one of the 154 sonnets that he penned during his career, explores the theme of time’s effect on beauty, youth, and the human condition. The sonnet is characterized by its melancholic meditation on the fleeting nature of physical beauty and the imperative for procreation to preserve one’s legacy and to combat the ravages of time. Shakespeare uses this sonnet to reflect on mortality, emphasizing the transitory nature of human life and the potential for immortality through the offspring of the beautiful.

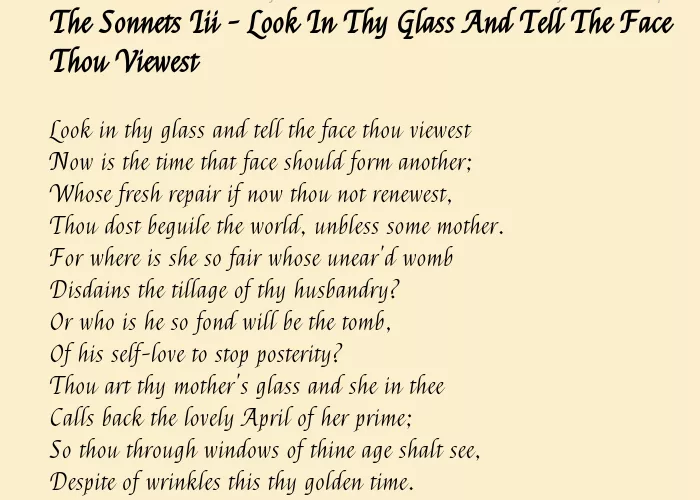

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 3

Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest,

Now is the time that face should form another,

Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest,

Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother.

For where is she so fair whose uneared womb

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

Or who is he so fond will be the tomb

Of his self-love, to stop posterity?

Thou art thy mother’s glass, and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime;

So thou through windows of thine age shalt see,

Despite of wrinkles, this thy golden time.

But if thou live rememb’red not to be,

Die single, and thine image dies with thee.

Structure and Theme

Sonnet 3 follows the traditional Shakespearean sonnet form: 14 lines written in iambic pentameter, with a rhyme scheme of ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. This structure, often used by Shakespeare, allows the poet to explore complex ideas within a disciplined framework, which in this sonnet serves to emphasize both the argument and the resolution that unfolds in the closing couplet.

The poem opens with a powerful statement about the inevitability of aging and decay. Shakespeare addresses the “fair youth” (a common reference to the young man whom many scholars believe Shakespeare admired and possibly loved), telling him that his beauty, like all youthful allure, will eventually fade. This idea of beauty fading with time forms the backbone of the sonnet’s argument.

Line-by-Line Analysis

In the opening quatrain, Shakespeare sets the stage for his exploration of beauty’s fragility. He writes:

- “When I consider everything that grows

- Holds in perfection but a little moment,

- That this huge stage presenteth nought but shows

- Whereon the stars in secret influence comment.”

Here, Shakespeare reflects on the brevity of all things that grow or exist. He acknowledges that beauty, whether physical or spiritual, is fleeting. The phrase “holds in perfection but a little moment” reveals the paradox of beauty: it is at its peak for a brief time before it starts to fade, making its permanence an illusion. Shakespeare also alludes to the “huge stage” of the world, a metaphor suggesting that life itself is a performance where each individual’s moment of brilliance is ephemeral. The “stars in secret influence comment” may allude to astrological beliefs of the time, wherein the stars’ positions were thought to influence human affairs. This reinforces the sense of inevitability, that one’s beauty and life are governed by forces beyond human control.

In the second quatrain, Shakespeare turns to the concept of immortality:

- “And having climb’d the steep-up heavenly hill,

- Resembl’d soaring phoenix with one true flame,

- Who, not contented with his burning, fill’d

- With this demise, a second time consumes his fame.”

Here, Shakespeare draws on the classical image of the phoenix, a bird that is reborn from its own ashes. This metaphor emphasizes the regenerative power of procreation—just as the phoenix consumes itself to rise again, so too can human beauty be immortalized through the act of having children. The idea that the “one true flame” is consumed only to renew itself links the theme of regeneration with the physical and moral legacy left through offspring.

The third quatrain brings a more direct argument:

- “O, that you were yourself! But, love, you are

- No longer yours, your self grows old and dies,

- But if you leave your children to be heir,

- You shall continue your beauty through their eyes.”

Here, Shakespeare bluntly tells the young man that his beauty will fade with time, but that through his children, his beauty and legacy can be preserved. The poet suggests that by procreating, the young man can live on through the next generation, and their beauty will serve as a testament to the beauty of the father. This is a deeply paternal, yet humanistic, sentiment—one that emphasizes the continuation of one’s identity beyond the constraints of mortality.

The Closing Couplets

In the final couplet, Shakespeare provides both a moral lesson and a bittersweet resolution:

“This fair child of mine, would in a son

In this world endure, so that his beauty shall be thine.”

Here, the poet suggests that by having children, the fair youth will create an “heir” who will bear his beauty and therefore preserve it for future generations. Shakespeare’s focus on beauty here is not purely aesthetic—it is symbolic of the enduring qualities of youth and life. Through children, the fleeting nature of personal beauty can be defied, creating a kind of immortality that transcends the individual’s temporal existence.

Conclusion

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 3 is a profound meditation on the inevitability of aging, the ravages of time, and the role of procreation in achieving a kind of immortality. The sonnet speaks not only to the transience of physical beauty but also to the possibility of transcending the boundaries of mortality through the legacy left in children. Through the metaphors of the phoenix and the “fair child,” Shakespeare elevates the concept of parenthood as a means of preserving both personal legacy and beauty. Ultimately, the sonnet’s message is that while beauty and youth are impermanent, the act of procreation offers a form of enduring continuity, giving the individual a chance at immortality through the next generation. This powerful theme resonates with Shakespeare’s broader concerns about the passage of time, legacy, and the human desire to leave an indelible mark on the world.