Shakespeare’s Sonnet 12, a part of the Fair Youth sequence, explores themes of the passage of time, the fleeting nature of beauty, and the inevitability of aging. As with many of Shakespeare’s sonnets, it reflects a deep awareness of mortality, making the poem not only a meditation on time but also a philosophical exploration of how beauty and life fade with it. In this essay, I will offer a detailed analysis of the structure and tone of the poem, followed by a paragraph-by-paragraph analysis.

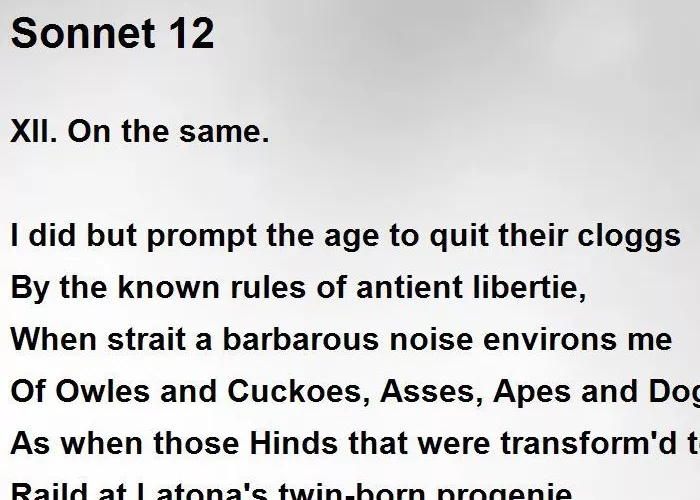

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 12

When I do count the clock that tells the time

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night,

When I behold the violet past prime

And sable curls all silvered o’er with white;

When lofty trees I see barren of leaves,

Which erst from heat did canopy the herd,

And summer’s green all girded up in sheaves

Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard;

Then of thy beauty do I question make

That thou among the wastes of time must go,

Since sweets and beauties do themselves forsake

And die as fast as they see others grow;

And nothing ’gainst Time’s scythe can make defense

Save breed, to brave him when he takes thee hence.

The Structure and Tone of Sonnet 12

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 12 is structured in the traditional form of the English sonnet: 14 lines of iambic pentameter, with the rhyme scheme ABABCDCDEFEFGG. This structure allows for a clear division between the three quatrains and the concluding couplet, which are typical in Shakespeare’s sonnet sequence.

The tone of the sonnet is meditative and reflective, suffused with a sense of melancholy and inevitability. The poet observes the passage of time with both a lament for what is lost and a recognition that it is an unstoppable force. The emotional weight of the poem is underpinned by the vivid imagery of decay and the aging process, yet the final couplet offers a glimmer of hope through the idea of procreation as a means of preserving beauty.

Sonnet 12 Analysis

Lines 1–4:

“When I do count the clock that tells the time,

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night;

When I behold the violet past prime,

And sable curls all silvered o’er with white;”

In the first quatrain, Shakespeare introduces the theme of time through the metaphor of a clock. The act of “counting the clock” suggests that time is something measurable and inevitable. The “brave day” sinking into “hideous night” is a metaphor for the transition from youth and vitality to old age and death. The word “hideous” implies that night, symbolizing aging and death, is an unwelcome force. The poet also reflects on the beauty of a “violet past prime,” a reference to the fading of youthful beauty, further emphasizing the passage of time. Similarly, the image of “sable curls all silvered o’er with white” symbolizes the graying of hair, a common sign of aging. Here, the imagery conveys both the natural beauty of youth and the inevitable decay that comes with time.

Lines 5–8:

“Then of thy beauty do I question make,

That thou among the wastes of time must go;

Since sweets and beauties do themselves forsake,

And die as fast as they see others grow.”

In these lines, the speaker turns directly to the Fair Youth, questioning the permanence of his beauty. The phrase “among the wastes of time” implies that the youth, like all humans, will eventually succumb to the ravages of time, leading to the inevitable fading of beauty. The speaker acknowledges that beauty is fleeting—“sweets and beauties do themselves forsake”—and that as new life emerges, older beauty must fade. The rhetorical structure here enhances the sense of inevitability; no one can escape the passage of time, regardless of their beauty or status.

Lines 9–12:

“And nothing ‘gainst Time’s scythe can make defence

Save breed, to brave him when he takes thee hence.

O, how much more doth beauty beauteous seem

By that sweet ornament which truth doth give!”

The ninth line introduces the image of Time as a figure wielding a “scythe,” a classical representation of death and mortality. The speaker acknowledges that there is no defense against the scythe of time except for “breed” — procreation. In this context, “breed” refers to offspring, which allows beauty to be perpetuated through the generations. The speaker then meditates on how beauty seems more beautiful when it is “ornamented” by truth. This refers to the idea that truth, or the continuation of one’s lineage, can make beauty seem more valuable, as it ensures that beauty is not lost to time. This reflects the idea of immortality through offspring, which is a theme that appears in several of Shakespeare’s sonnets.

Lines 13–14:

“Make thee another self for love of me,

That beauty still may live in thine or thee.”

The concluding couplet provides a resolution to the poem’s earlier meditation on the passage of time and beauty. The speaker urges the Fair Youth to procreate—to “make thee another self”—so that his beauty may be preserved in future generations. In doing so, the youth’s beauty will continue to “live,” both in his children and in the memory of others. There is a strong sense of love and affection in the final lines, as the speaker suggests that the youth should continue his legacy not for personal gain, but for the sake of love.

Conclusion

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 12 is a powerful reflection on time, aging, and beauty. The poem’s structure allows the speaker to progress logically from a meditation on the passage of time to a more hopeful conclusion that advocates for procreation as a means of preserving beauty. Through vivid imagery and philosophical reflection, the poem explores the inevitability of time while offering a resolution that connects beauty, truth, and love. Ultimately, the sonnet suggests that while time will diminish physical beauty, the act of creating life offers a form of immortality, allowing beauty to transcend death.