William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 14 is a profound exploration of the limits of astrology and fate, shifting the focus of understanding from celestial bodies to human agency. The sonnet captures the conflict between the external forces that often govern life and the inner, personal power derived from love and individual connection. Shakespeare’s use of structure and tone in this poem directs the reader’s attention to the human soul and the transformative effect of genuine emotion.

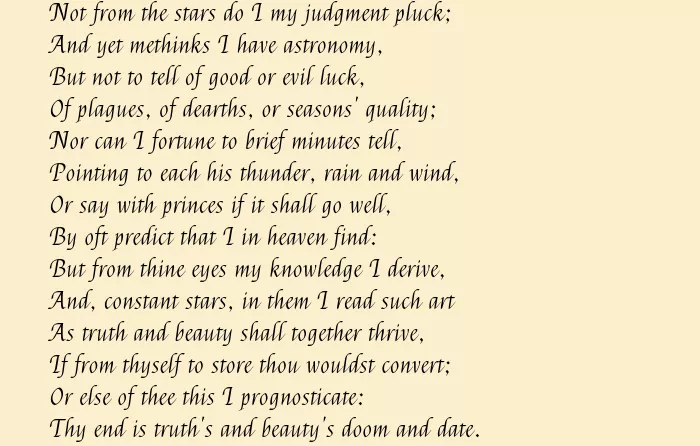

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 14

Not from the stars do I my judgment pluck,

And yet methinks I have astronomy—

But not to tell of good or evil luck,

Of plagues, of dearths, or seasons’ quality;

Nor can I fortune to brief minutes tell,

Pointing to each his thunder, rain, and wind,

Or say with princes if it shall go well

By oft predict that I in heaven find.

But from thine eyes my knowledge I derive,

And, constant stars, in them I read such art

As truth and beauty shall together thrive

If from thyself to store thou wouldst convert;

Or else of thee this I prognosticate:

Thy end is truth’s and beauty’s doom and date.

The Structure and Tone of Sonnet 14

Sonnet 14 follows the traditional Shakespearean sonnet structure: 14 lines divided into three quatrains and a final rhymed couplet. The rhyme scheme is ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, a classic arrangement that provides both rhythm and emphasis. Each quatrain addresses a different aspect of the poet’s argument, with the final couplet offering a resolution or conclusion. Shakespeare uses iambic pentameter, the rhythmic foundation of his sonnets, which emphasizes the natural flow of the poem and gives it a stately, almost meditative tone.

The tone of Sonnet 14 is reflective and declarative. It begins with a strong assertion of independence from the typical tools of fortune-telling, specifically astrology, and gradually shifts to a more personal, intimate reflection on the poet’s understanding of fate. This creates a sense of conviction, as Shakespeare argues for a more authentic form of knowledge derived from love, trust, and personal insight, rather than external, impersonal predictions.

Analysis of the Sonnet 14

Lines 1–4

“Not from the stars do I my judgment pluck,

And yet methinks I have astronomy—

But not to tell of good or evil luck,

Of plagues, of dearths, or seasons’ quality;”

In the first quatrain, Shakespeare opens with a clear rejection of astrology as a means of discerning the future. The phrase “Not from the stars do I my judgment pluck” serves as an immediate repudiation of the traditional belief that celestial bodies control earthly events. He acknowledges, however, that he does possess a kind of astronomy—but it is not the fortune-telling astronomy that predicts luck or earthly disasters. This sets the tone for the poem as one that critiques fate’s perceived control over human life. Instead of relying on the stars, Shakespeare’s astronomy will be a more personal, human-centered understanding of the world.

Lines 5–8

“Nor can I fortune to brief minutes tell,

Pointing to each his thunder, rain, and wind,

Or say with princes if it shall go well

By oft predict that I in heaven find.”

Here, Shakespeare continues his disavowal of astrology and fate. The phrase “fortune to brief minutes tell” emphasizes the transitory and fleeting nature of predicting events with precision. The speaker further distances himself from the idea that he can forecast personal events or the whims of rulers, dismissing the idea of astrology as a reliable source of prophecy. Shakespeare’s critique suggests that such predictions are arbitrary and not rooted in the deeper truths of human existence.

Lines 9–12

“But from thine eyes my knowledge I derive,

And, constant stars, in them I read such art

As truth and beauty shall together thrive

If from thyself to store thou wouldst convert;”

The third quatrain marks a shift toward a more positive and intimate view of knowledge and truth. Instead of relying on the stars or external forces, the speaker claims that his knowledge comes from the beloved’s eyes—“constant stars” in themselves. This metaphor suggests that love, truth, and beauty reside within the beloved, and by looking into their eyes, the poet can perceive these eternal qualities. The idea of conversion here refers to the beloved turning their beauty and truth inward, to store it, preserving its purity. This suggests that the true, lasting wisdom comes not from the heavens but from human connection and the integrity of one’s inner self.

Lines 13–14

“Or else of thee this I prognosticate:

Thy end is truth’s and beauty’s doom and date.”

In the final couplet, Shakespeare delivers a powerful prognostication, but one rooted in love rather than astrology. If the beloved does not preserve their beauty and truth, then they face the inevitable doom of losing both. This is a dire warning, yet it emphasizes the fragility of these virtues and the importance of protecting them. Shakespeare uses the word “doom” not in a fatalistic sense, but rather to indicate that neglecting truth and beauty will lead to their destruction. The final lines shift the focus back to the idea of personal agency, implying that the beloved’s fate lies not in the hands of the stars, but in their own choices.

Conclusion

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 14 is a profound reflection on the nature of fate and human agency. The speaker rejects the traditional reliance on astrology and fortune-telling, instead finding knowledge and understanding in the eyes of the beloved. The metaphor of the “constant stars” represents the enduring power of love, truth, and beauty, suggesting that these internal, human qualities transcend the whims of external forces. The final couplet serves as a warning that these virtues must be preserved, for their loss would lead to the inevitable collapse of one’s personal truth and beauty. Ultimately, Sonnet 14 is a meditation on the importance of human connection and the way it can offer a more genuine and lasting form of knowledge than the stars or the shifting fortunes of life.