William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 17 is a rich and contemplative piece of poetry, which, like many of his sonnets, explores themes of love, time, and the preservation of beauty through art. The sonnet is deeply self-aware, as it grapples with the challenge of capturing a lover’s beauty in words. While it has the typical structure of a Shakespearean sonnet—composed of 14 lines written in iambic pentameter with the rhyme scheme ABAB CDCD EFEF GG—its underlying tone and the philosophical depth of the poem set it apart.

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 17

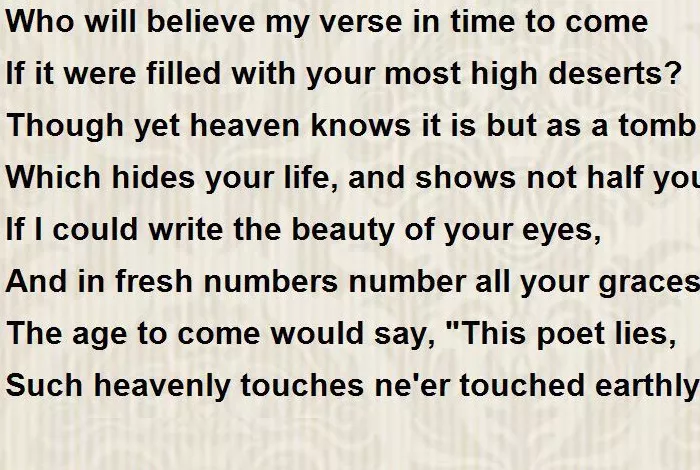

Who will believe my verse in time to come

If it were filled with your most high deserts?

Though yet, heaven knows, it is but as a tomb

Which hides your life and shows not half your parts.

If I could write the beauty of your eyes

And in fresh numbers number all your graces,

The age to come would say “This poet lies;

Such heavenly touches ne’er touched earthly faces.”

So should my papers, yellowed with their age,

Be scorned, like old men of less truth than tongue,

And your true rights be termed a poet’s rage

And stretchèd meter of an antique song.

But were some child of yours alive that time,

You should live twice—in it and in my rhyme.

The Structure and Tone of Sonnet 17

Sonnet 17 adheres to the traditional Shakespearean sonnet form, with three quatrains and a final rhymed couplet. The first three quatrains build up the central tension of the poem, while the concluding couplet offers a resolution.

The tone of the poem is one of sorrowful uncertainty mixed with a kind of resignation. Shakespeare’s speaker, addressing a mysterious “you,” laments that even the most beautiful verse may fail to immortalize the beloved’s beauty. The speaker recognizes that time will obscure his attempts to preserve this beauty. However, the final couplet offers a hopeful resolution, suggesting that the true immortality of the beloved can be achieved not through art alone, but through the procreation of an heir.

Now, let’s break down and analyze the individual stanzas of the poem in greater detail.

Analysis of Sonnet 17

Lines 1–4

“Who will believe my verse in time to come

If it were filled with your most high deserts?

Though yet, heaven knows, it is but as a tomb

Which hides your life and shows not half your parts.”

In the first quatrain, the poet begins with an expression of doubt about the future reception of his verse. The phrase “Who will believe my verse in time to come” introduces a sense of uncertainty, as the speaker contemplates the likelihood of future readers appreciating his poetry. Shakespeare addresses the beloved directly, suggesting that even if the poem were filled with the “high deserts” (exalted qualities) of the lover, it would still fail to capture the full essence of their beauty.

The metaphor of the poem being “but as a tomb” is a poignant reflection on the limitations of art. Just as a tomb holds the remains of a person but does not truly preserve their full vitality, the speaker suggests that poetry, no matter how beautiful, can only contain a fraction of the lover’s life and spirit. The phrase “shows not half your parts” implies that the written word can never do justice to the beloved’s complete beauty.

Lines 5–8

“If I could write the beauty of your eyes

And in fresh numbers number all your graces,

The age to come would say “This poet lies;

Such heavenly touches ne’er touched earthly faces.”

In the second quatrain, the speaker imagines a hypothetical scenario where he could perfectly capture the beloved’s beauty in verse. Specifically, he wishes he could describe the “beauty of your eyes” and catalog all the lover’s virtues (“number all your graces”). However, he recognizes that even such a perfect description would be met with skepticism in the future.

The phrase “The age to come would say ‘This poet lies'” suggests that even if the poet succeeded in painting an idealized portrait of the beloved, future generations would reject it as unbelievable. The “heavenly touches” mentioned here are qualities so divine that they seem unattainable for a mortal being. The speaker laments that earthly beauty, as he perceives it, could never live up to the celestial ideal, and thus poetry would be dismissed as a lie, an exaggeration of earthly experience.

Lines 9–12:

“So should my papers, yellowed with their age,

Be scorned, like old men of less truth than tongue,

And your true rights be termed a poet’s rage

And stretchèd meter of an antique song.”

The third quatrain continues the theme of time’s inevitable decay. The speaker contemplates how his written words will eventually become aged and irrelevant, just as old men who lose their credibility are dismissed as “having less truth than tongue.” Shakespeare connects the fading truth of his poetry with the way society often disregards the voices of the elderly. The metaphor of “yellowed papers” symbolizes the decay of the written word over time.

Moreover, the speaker fears that the “true rights” of the beloved will be reduced to nothing more than poetic embellishment—a “poet’s rage” or an exaggerated claim through “stretchèd meter.” In other words, the speaker anticipates that, over time, his verse will be considered nothing more than a melodramatic or artificial attempt to elevate the lover’s beauty.

Lines 13–14 (The Couplet)

“But were some child of yours alive that time,

You should live twice—in it and in my rhyme.”

The final couplet resolves the tension introduced throughout the sonnet. Here, the speaker presents a vision of immortality achieved through the procreation of an heir. The child would carry on the lover’s physical existence in the future, while the speaker’s verse would preserve their spiritual and artistic legacy. This idea of living “twice” suggests that true immortality is found not in art alone, but in the continuation of life through offspring.

This couplet functions as a shift in tone, from the despair over the impermanence of art to the hopeful realization that the beloved’s legacy can be preserved not just in poetry, but through biological inheritance. The coupling of the biological and artistic continuations of the lover’s beauty suggests that poetry, while ephemeral, can still play a significant role in ensuring the survival of the beloved’s essence.

Conclusion

Sonnet 17 is a poignant reflection on the limitations of art in capturing the full spectrum of human beauty. Shakespeare acknowledges that time will erode even the most perfect verse, rendering it obsolete and unconvincing to future generations. The poet’s dilemma—how to immortalize a love so exquisite that words cannot truly do it justice—lies at the heart of this sonnet. However, through the final couplet, Shakespeare provides a solution: the beloved’s true immortality lies not solely in art but in the continuation of life through progeny. Thus, Sonnet 17 highlights the tension between the fleeting nature of art and the enduring legacy of human life, suggesting that poetry’s role is not to surpass time, but to preserve it for future generations.