William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18, one of his most famous and enduring works, explores themes of love, beauty, and immortality. Through the use of vivid imagery, metaphor, and contrast, Shakespeare presents a timeless tribute to the beloved, declaring that their beauty will endure forever. To fully appreciate the depth of Sonnet 18, one must first consider its structure, tone, and the meaning conveyed in each individual quatrain.

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18

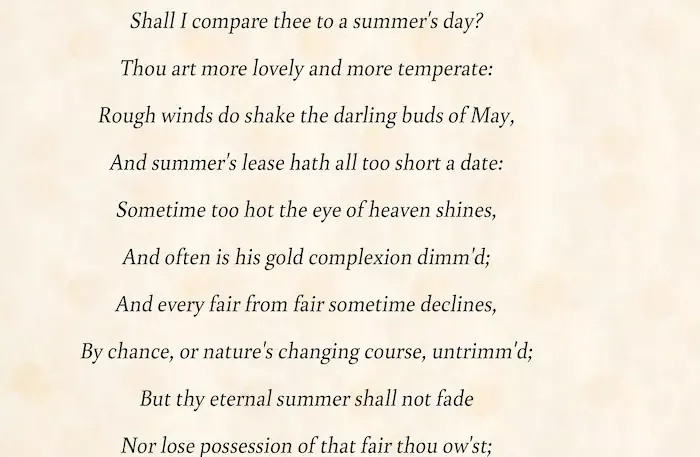

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date.

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance or nature’s changing course untrimmed.

But thy eternal summer shall not fade

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall Death brag thou wand’rest in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st.

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

The Structure and Tone of Sonnet 18

Sonnet 18 follows the traditional Shakespearean sonnet form, composed of 14 lines arranged in three quatrains (four-line stanzas) followed by a final rhymed couplet. The rhyme scheme is ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, which is typical of Shakespeare’s works. The meter is iambic pentameter, meaning each line consists of ten syllables, alternating between unstressed and stressed syllables.

The tone of Sonnet 18 shifts between admiring and reflective, with an underlying sense of reverence. At the beginning of the sonnet, the speaker contemplates comparing the beloved to a summer day, a common metaphor for beauty. However, as the poem progresses, the speaker reveals that the beloved surpasses a summer’s day in both beauty and eternal presence. There is also a shift from a temporary, natural world to the idea of something everlasting, with a strong sense of the speaker’s devotion and the power of poetry to immortalize beauty.

Analysis of Sonnet 18

Lines 1-4: The Summer Day Metaphor

“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date.”

The poem opens with the rhetorical question, “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” Shakespeare invites the reader into a contemplation of beauty and its transience. The question sets up a metaphor that would have been familiar in Elizabethan poetry, comparing human beauty to the fleeting perfection of summer.

However, the speaker quickly dismisses this comparison, stating that the beloved is “more lovely and more temperate” than a summer’s day. Summer, while beautiful, has its flaws—“rough winds” shake the buds in May, and summer is all too short-lived. Here, Shakespeare introduces the theme of impermanence. Summer, though an idealized season, is subject to the whims of nature, and its beauty cannot last forever. By contrast, the speaker’s beloved possesses a more stable, enduring beauty.

Lines 5-8: The Harshness of Nature

“Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance or nature’s changing course untrimmed.”

The second quatrain extends the metaphor of summer’s flaws. The “eye of heaven” refers to the sun, which at times shines “too hot,” and its “gold complexion” is often “dimmed,” either by clouds or the passage of time. Shakespeare alludes to the impermanence of physical beauty, stating that “every fair from fair sometime declines.” Even the most beautiful things must eventually fade due to “chance or nature’s changing course.”

This stanza deepens the contrast between the beloved’s beauty and the transient nature of the natural world. The use of the words “chance” and “nature’s changing course” suggests that beauty’s decline is often beyond human control, subject to forces outside of our influence.

Lines 9-12: The Immortalization of the Beloved

“But thy eternal summer shall not fade

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall Death brag thou wand’rest in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st.”

In the third quatrain, Shakespeare begins to shift focus from the natural world to the eternal, introducing the idea of the beloved’s beauty transcending time. The phrase “eternal summer” contrasts with the fading summer and fleeting human beauty discussed earlier. The speaker assures the beloved that their beauty will not fade, and they will never “lose possession” of it. Shakespeare here alludes to the power of poetry: the beloved will live on “in eternal lines,” meaning that the written word will immortalize their beauty, unaffected by the ravages of time or death.

The phrase “Nor shall Death brag thou wand’rest in his shade” is a powerful statement of defiance against mortality. Death, which takes all living things, will not be able to claim the beloved, as their beauty will continue to live on in the poem. Shakespeare uses the metaphor of death’s “shade,” which suggests the shadow of death, but here it is denied to the beloved.

Lines 13-14: The Immortality of the Poem

“So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.”

The final couplet brings the sonnet to its resolution, emphasizing the immortality of both the poem and the beloved. As long as there are humans to read or speak the poem, the beloved’s beauty will live on. The poem itself becomes a vessel for immortality, a medium through which the beloved will continue to exist in the consciousness of future generations. The line “this gives life to thee” encapsulates the central message of the sonnet: poetry has the power to grant eternal life and preserve beauty beyond the constraints of time.

Conclusion

Sonnet 18 is a profound meditation on love, beauty, and immortality. Through the comparison of the beloved to a summer’s day, Shakespeare introduces the concept of fleeting beauty and the natural decline of all things. However, the poem ultimately shifts from the transient world of nature to the enduring power of poetry. In the closing lines, Shakespeare asserts that through the written word, the beloved’s beauty will live on forever. In a sense, the sonnet itself becomes a testament to the idea that art, once created, can transcend time, granting a form of immortality to both the subject and the artist.