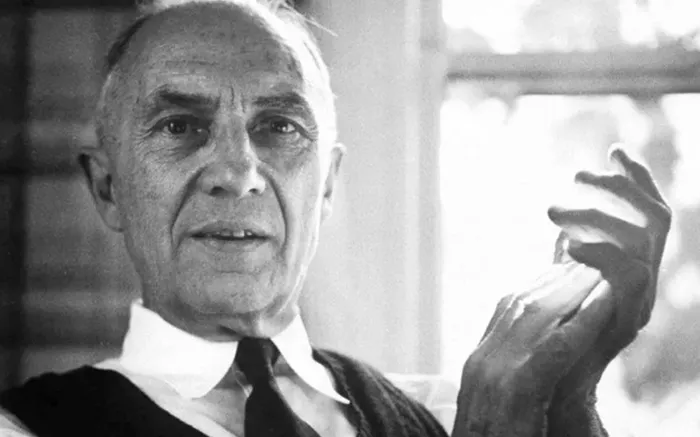

William Carlos Williams, a prominent figure in 20th-century American poetry, was a poet who reshaped the landscape of American verse with his distinctive approach to language, imagery, and structure. His work, often focused on the ordinary and the local, stands as a hallmark of modernist American poetry. His contributions to American literature were profound, particularly in his ability to combine an appreciation for the American experience with an innovative poetic form that sought to reflect the rhythms and cadences of everyday speech. Williams’s work defied convention, incorporating elements from a variety of literary movements and yet, simultaneously, standing apart from them. In this article, we will explore the life, style, influences, and legacy of Williams, illustrating how he became one of the defining poets of 20th-century American poetry.

Early Life and Influences

William Carlos Williams was born on September 17, 1883, in Rutherford, New Jersey, to a Puerto Rican mother and an American father. His bicultural background played a significant role in shaping his outlook on life and literature. Growing up in a household where English and Spanish were spoken, Williams developed an early sensitivity to the nuances of language. This linguistic awareness would become a central theme in his poetic career.

Williams was an avid reader from a young age, and although his early influences were diverse, they were rooted in the modernist movements of the early 20th century. In particular, Williams was drawn to the works of the Imagists and the Symbolists. Ezra Pound, the influential modernist poet, was one of Williams’s early mentors. Pound’s emphasis on precision, clarity, and economy of language had a profound impact on Williams, who adopted many of these principles in his own writing. However, while Williams shared many of the modernist concerns, he also developed his own unique voice, which was sometimes in opposition to the highbrow, intellectual nature of other modernists.

Williams’s Professional Career and Influence

In addition to being a poet, Williams was also a practicing physician. This dual career is perhaps one of the most distinctive aspects of his life, and it greatly influenced his work. Williams’s medical profession brought him into close contact with ordinary people, allowing him to witness the daily struggles and triumphs of the working class. This experience was crucial in shaping his vision of American poetry as something grounded in the everyday experiences of individuals.

His first published collection of poetry, Poems (1909), was initially not widely recognized. However, his career began to take off in the 1910s, with the publication of his landmark work Spring and All in 1923. This collection marked a turning point in Williams’s career, as he began to experiment with free verse and the use of imagery to convey the rhythms of everyday life. The book exemplified his desire to break away from the conventions of formal poetry and embrace a more natural, organic style.

In the years that followed, Williams continued to develop his poetic voice, experimenting with new forms and techniques. He published a number of important works throughout the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, including The Desert Music (1929), The Collected Poems (1938), and Paterson (1946). Paterson, perhaps his most famous work, is a long, complex poem that examines the American experience through a series of fragmented, dreamlike narratives. It is in Paterson that Williams fully embraces his idea of “localness”—the concept that poetry should be grounded in the everyday lives of the people and places that shape it.

Despite the challenges of being a poet in a rapidly changing world, Williams remained committed to his craft. His poetry often reflected the political and social issues of his time, from the aftermath of the Great Depression to the cultural shifts of the post-World War II era. He was not afraid to engage with the world around him, and his works are imbued with a deep sense of humanity and a desire to understand the complexities of modern life.

Williams’s Poetic Style

Williams is best known for his departure from the rigid structures of traditional poetry. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he was uninterested in adhering to rhyme and meter. Instead, he focused on free verse and the natural rhythms of speech. His work was also marked by his use of vivid, often stark imagery. The precision of his language is one of his most defining characteristics, and he often employed the most direct language possible to capture the essence of an experience.

One of Williams’s most famous lines comes from his poem The Red Wheelbarrow:

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens.

In this deceptively simple poem, Williams captures a moment of quiet observation. The image of the red wheelbarrow, which might seem mundane to some, is imbued with a sense of importance and beauty. Williams’s focus on the small, everyday objects of life set him apart from other poets of his time, who often sought grandeur or symbolism in their work.

The concept of the “American poem” was central to Williams’s thinking. He believed that American poetry should not be an imitation of European forms but should instead reflect the landscape, language, and culture of the United States. For Williams, this meant focusing on the physicality of the American landscape, as well as the rhythms of American speech. In poems such as In the American Grain (1925) and The Great Figure (1921), Williams explores the American experience, from the urban setting of the city to the rural life of the American heartland.

The Role of Localism in Williams’s Poetry

One of the key themes in Williams’s work is his focus on localism. He believed that poetry should be rooted in the specific, the local, and the particular. This can be seen in his portrayal of the American landscape, which often reflects the details of everyday life in specific locations. Williams’s emphasis on locality was a radical departure from the more universal concerns of many of his contemporaries.

In Paterson, Williams’s most ambitious work, he explores the city of Paterson, New Jersey, as a microcosm of the American experience. Through the fragmented, often disjointed narrative of Paterson, Williams seeks to capture the essence of American life in all its complexity. The city itself becomes a symbol of the larger American experience, and Williams’s focus on the local allows him to engage with the universal in a way that is both personal and deeply rooted in the specific.

This focus on localism is also present in his depiction of American people. Williams was particularly interested in the lives of ordinary people—the working-class men and women who shaped the country’s identity. His poems often give voice to these individuals, portraying them with empathy and respect. In doing so, Williams sought to create a poetry that was inclusive and representative of all aspects of American life.

Williams’s Legacy and Influence

Williams’s impact on American poetry is immeasurable. His work influenced generations of poets who followed in his wake, from the Beat poets of the 1950s to the confessional poets of the 1960s. His insistence on the importance of the local, his focus on the rhythms of speech, and his commitment to capturing the essence of the American experience resonated deeply with many writers.

One of the poets most influenced by Williams was Allen Ginsberg, who saw in Williams’s work a model for his own writing. Ginsberg’s Howl (1956) and other works were influenced by Williams’s commitment to free verse and his exploration of the American landscape. Ginsberg, along with poets such as Gregory Corso and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, helped to popularize the more experimental, free-flowing style of poetry that Williams had pioneered.

Williams’s influence can also be seen in the work of poets such as Denise Levertov, John Ashbery, and James Wright. These poets, while distinct in their own right, drew on Williams’s emphasis on localism, his focus on the ordinary, and his use of free verse. Williams’s work, therefore, continued to shape the course of American poetry long after his death.

Conclusion

William Carlos Williams was a poet who redefined the boundaries of American poetry in the 20th century. His emphasis on free verse, his focus on the ordinary, and his commitment to capturing the rhythms of American speech made him one of the most important figures in modernist literature. Through his work, Williams sought to create a poetry that was both accessible and deeply reflective of the American experience. Today, Williams’s influence continues to be felt in the work of contemporary poets, and his legacy endures as a cornerstone of 20th-century American poetry. Whether through his depiction of the American landscape, his focus on localism, or his innovative use of language, Williams remains a key figure in the evolution of modern poetry. His works, filled with precision, empathy, and a deep understanding of the human condition, continue to inspire readers and writers alike.