Welcome to Poem of the Day – To The Accuser To Mr. Cyriack Skinner Upon His Blindness by John Milton.

John Milton’s To Mr. Cyriack Skinner Upon His Blindness stands as one of his most personal and philosophically rich shorter poems. Written during a time when Milton had already lost his own sight, the poem responds to the blindness of his friend, Cyriack Skinner. Despite the poem’s relatively compact structure, it offers a deep meditation on the nature of suffering, resilience, and the relationship between physical and spiritual vision. Through his exploration of these themes, Milton addresses both the personal anguish of blindness and the larger, transcendent power of faith, intellectual purpose, and duty.

In this essay, we will explore how Milton reflects on the experience of blindness, using it as a metaphor for broader human suffering and the possibility of moral and spiritual enlightenment. Additionally, the poem’s underlying theme of liberty—Milton’s own sacrifice for the defense of freedom—is central to its meaning. As a British poet, Milton’s vision of resilience in the face of hardship speaks to both the individual and the collective, revealing the power of the human spirit even in the absence of physical sight.

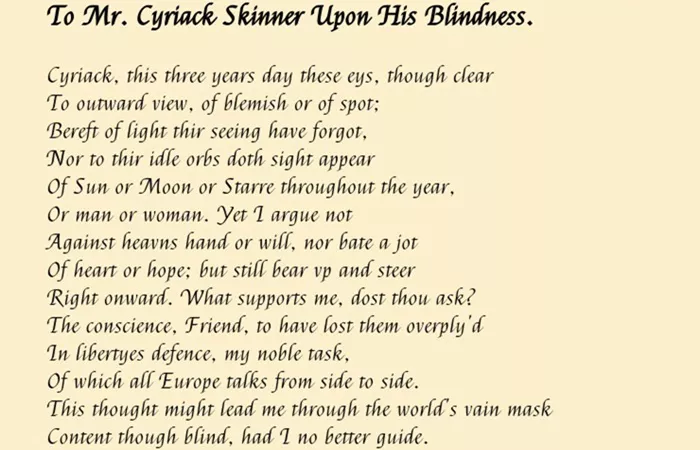

To The Accuser To Mr. Cyriack Skinner Upon His Blindness Poem

Cyriack, this three years day these eys, though clear

To outward view, of blemish or of spot;

Bereft of light thir seeing have forgot,

Nor to thir idle orbs doth sight appear

Of Sun or Moon or Starre throughout the year,

Or man or woman. Yet I argue not

Against heavns hand or will, nor bate a jot

Of heart or hope; but still bear vp and steer

Right onward. What supports me, dost thou ask?

The conscience, Friend, to have lost them overply’d

In libertyes defence, my noble task,

Of which all Europe talks from side to side.

This thought might lead me through the world’s vain mask

Content though blind, had I no better guide.

To The Accuser To Mr. Cyriack Skinner Upon His Blindness Explanation

The poem consists of ten lines written in iambic pentameter, a metrical form that Milton often employed throughout his career. Although the poem does not adhere strictly to the sonnet form, its brevity and lyrical quality give it the compact, philosophical nature of a Petrarchan sonnet. The meter itself, along with the careful rhyme scheme, lends a sense of order and deliberation to the poem, which reflects the intellectual rigor Milton applied to his reflections on his blindness.

Milton uses the structure of the poem to express not only his own thoughts but also to offer consolation and moral insight to his friend, Cyriack Skinner. The poem is filled with both personal introspection and universal reflection, and its form allows Milton to probe both the physical and the metaphysical aspects of blindness, moving from personal lamentation to philosophical reflection and ultimately to a celebration of resilience and faith.

The Experience of Blindness: Personal and Philosophical

In the opening lines, Milton addresses his friend Cyriack Skinner, introducing the theme of blindness with a personal and immediate resonance. Milton describes how, despite the outward appearance of his eyes as being “clear,” they have become “bereft of light,” unable to perceive the sun, moon, stars, or even people. The contrast between the clear outward appearance and the inner absence of sight emphasizes the emotional and spiritual pain of losing such a vital sense:

“Cyriack, this three years’ day these eyes, though clear

To outward view, of blemish or of spot;

Bereft of light their seeing have forgot,

Nor to their idle orbs doth sight appear…”

The sense of loss here is immediate and profound. Milton suggests that, although the eyes themselves may appear unchanged, the soul or spirit suffers because of the absence of light. The metaphor of “light” here is not only a physical one, but also a spiritual one, representing knowledge, understanding, and insight—values that were deeply meaningful to Milton, particularly as a writer and political thinker.

However, the key message here is that Milton does not resign himself to bitterness or regret. Instead, he asserts that the loss of sight has not led him to despair. He writes:

“Yet I argue not

Against heaven’s hand or will, nor bate a jot

Of heart or hope; but still bear up and steer

Right onward.”

This affirmation of endurance and resolve signals a central theme in the poem: despite the seemingly insurmountable difficulty of blindness, Milton maintains hope and faith. The decision to “bear up and steer / Right onward” reflects the poet’s determination to persist despite suffering, which echoes the Puritan values of endurance and faith in God’s greater plan. This perspective is significant, as Milton’s Puritan faith taught that adversity was part of God’s will and, therefore, must be accepted with grace.

Liberty as the Guiding Principle

One of the most important themes of the poem is Milton’s assertion that his blindness is a worthy sacrifice in the service of liberty. Milton introduces the idea that the loss of his sight has not diminished his sense of purpose or his moral resolve. Instead, he draws strength from the thought that his blindness came as a consequence of his work in the defense of liberty, a cause he deemed noble and essential:

“What supports me, dost thou ask?

The conscience, Friend, to have lost them overply’d

In liberty’s defence, my noble task,

Of which all Europe talks from side to side.”

Here, Milton offers the concept of liberty not merely as a political cause but as a moral and intellectual one. By aligning his blindness with his efforts to protect and promote liberty, Milton redefines blindness as something that serves a greater purpose. His spiritual vision, informed by his commitment to freedom, compensates for his loss of physical sight. This idea reinforces Milton’s belief in the connection between personal sacrifice and the greater good. His loss, then, becomes a marker of personal virtue, an act of moral integrity in the service of a higher cause.

Milton further emphasizes that this “noble task” was not a private endeavor but one of public importance, noted by all of Europe. By doing so, Milton places his blindness within the framework of historical and global significance, elevating his personal affliction to a symbol of broader sacrifice for the ideals of freedom and justice.

The Mask of the World and the Power of Faith

Milton closes the poem with a final, poignant meditation on the possibility of finding contentment despite being blind. The poet suggests that, although blindness may obscure the material world, it cannot obscure the soul’s connection to higher truths:

“This thought might lead me through the world’s vain mask

Content though blind, had I no better guide.”

The phrase “the world’s vain mask” reflects Milton’s disdain for the superficiality of the material world. The “mask” suggests a deception or illusion, further deepening Milton’s sense of disillusionment with the world he can no longer physically see. Yet, he also expresses that even in the midst of this disillusionment, he can find contentment, provided he has the “better guide” of faith and moral purpose. This is a crucial point: for Milton, even physical blindness cannot rob him of his inner vision or the guiding principles of virtue and faith. His “better guide” refers to a higher moral and spiritual compass, which he believes transcends the physical realm and offers a deeper kind of sight.

This reliance on spiritual insight rather than material perception is a hallmark of Milton’s broader philosophical and theological outlook. It reflects his belief in the power of the human soul and its capacity for insight and understanding, even when physical senses are impaired.

Conclusion

To Mr. Cyriack Skinner Upon His Blindness is a meditation on the complexities of blindness, not just as a physical condition but as a metaphor for deeper intellectual and spiritual challenges. Through the poem, Milton presents blindness as a condition that can either limit or empower the individual. For Milton, it is through faith, virtue, and a commitment to higher principles like liberty that the individual can transcend the apparent limitations of the physical world.

Milton’s work speaks to the resilience of the human spirit and the enduring capacity for intellectual and moral vision, even in the face of adversity. By framing his personal suffering within a broader philosophical context, Milton transforms the experience of blindness into an emblem of strength, purpose, and grace. His faith in divine purpose, his commitment to liberty, and his belief in the guiding power of the soul ultimately offer a message of hope and resilience that remains deeply resonant.

As a British poet, Milton’s exploration of suffering, resilience, and spiritual vision offers profound insight into the human condition, making To Mr. Cyriack Skinner Upon His Blindness an enduring work of both personal and universal significance.