[pb]1[/pb], a name that might not immediately strike a chord with those unfamiliar with the intricacies of Japanese literature, remains an important figure within the annals of 13th-century Japanese poetry. Living during the late Heian to early Kamakura period, Kunai-kyō’s contributions to Japanese poetry reflect the dramatic shifts in culture and society of that era. His poetic style and themes were influenced by the social turmoil, the rise of the samurai class, and the evolving Buddhist ethos of the time.

This article aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of Kunai-kyō’s work, his significance in the broader context of 13th-century Japanese poets, and how his poetry compares to other figures of his time, such as the renowned poets Fujiwara Teika and Jien.

The Historical Context of Kunai-kyō’s Life and Poetry

Kunai-kyō lived during a period of significant change in Japan. The late Heian period (794–1185) was characterized by the dominance of the imperial court and aristocratic culture. However, by the 13th century, the rise of the samurai class and the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate (1185) marked a profound shift in Japanese society. The power structures were shifting from a focus on courtly refinement to the warrior class and military governance.

The early Kamakura period, in particular, saw the influence of Zen Buddhism, which began to permeate the culture. Many poets, including Kunai-kyō, were influenced by these changing times. Kunai-kyō’s life span—roughly from the mid-12th century to his death in 1207—placed him at the crossroads of these significant cultural transitions. This context played a crucial role in shaping his poetic voice and thematic concerns.

The Life of Kunai-kyō

While much of Kunai-kyō’s life remains shrouded in mystery, several details about him have come down through historical texts. His given name is not entirely clear, as “Kunai-kyō” could have been a pen name. However, some scholars suggest he may have been a member of the Fujiwara family, which had a long and illustrious connection to the imperial court.

Kunai-kyō’s life seems to have been influenced by his proximity to the aristocratic and religious circles of the time. He was a member of the literati, a group of individuals who excelled in poetry, calligraphy, and other intellectual pursuits. It is believed that his work was deeply affected by the courtly aesthetic of the Heian period, but also by the tumultuous political climate of the early Kamakura period, a time when the samurai’s power was increasing.

Kunai-kyō’s Poetic Style and Themes

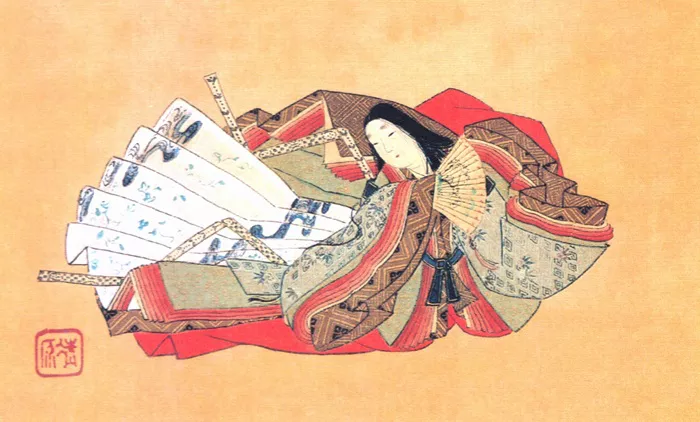

Kunai-kyō’s poetry is typically associated with the traditional forms of Japanese verse, such as waka, a 31-syllable form that was the dominant mode of expression in Heian and early Kamakura Japan. His style is marked by the classic use of kakekotoba (pivot words), makurakotoba (pillow words), and kenjōgo (humble language), which were hallmarks of the courtly poetic tradition. His works, often elegiac in tone, reflect a deep sense of impermanence, a theme that resonates throughout much of Japanese poetry, particularly in the face of social upheaval.

The influence of Buddhism on his poetry is unmistakable. Buddhism, with its teachings on impermanence (mujo), suffering (dukkha), and the cycle of life and death, was increasingly important during the 13th century. In Kunai-kyō’s work, this is evident in his frequent meditation on the fleeting nature of beauty, life, and human relationships.

One of the central motifs in Kunai-kyō’s poetry is the notion of transience. He often used images of nature, such as the falling of cherry blossoms or the passing of seasons, to symbolize human mortality. This theme of impermanence was not unique to Kunai-kyō but was a shared concern among many poets of the period.

In comparison, other 13th-century Japanese poets, such as Fujiwara Teika, were more focused on preserving the ideals of the Heian courtly tradition. Teika, for instance, was primarily concerned with maintaining the formal aspects of waka poetry and the importance of poetic refinement. Kunai-kyō, on the other hand, while maintaining the structural conventions, was more focused on the deeper, often spiritual aspects of life, reflecting the growing influence of Zen Buddhism during the period.

Kunai-kyō and His Contemporary Poets

To better understand Kunai-kyō’s place in the landscape of 13th-century Japanese poetry, it is helpful to examine his contemporaries and their literary contributions.

Fujiwara Teika (1162–1241): Known for his involvement in the shinkokinshū (New Collection of Japanese Poems), Teika was one of the leading figures in the poetry of the late Heian and early Kamakura periods. His poetry is characterized by a highly refined sense of aestheticism, marked by complex metaphors, allusions, and an emphasis on the beauty of nature. While Kunai-kyō shared Teika’s reverence for nature, Kunai-kyō’s works are often more introspective, focusing on Buddhist themes of impermanence and the ephemeral nature of human existence.

Jien (1155–1225): A Buddhist priest and poet, Jien was a key figure in the early Kamakura period. Jien’s poetry reflects the influence of his religious life, with many of his poems exploring Buddhist concepts of mujo (impermanence) and zazen (meditative sitting). Like Kunai-kyō, Jien’s work shows a profound engagement with the impermanence of life, but Jien’s poetry is more philosophical and direct in its expressions of Buddhist doctrine, whereas Kunai-kyō’s work is more emotive and personal.

Kunai-kyō’s work, while sharing thematic elements with these poets, was also distinguished by a particular focus on the personal and the emotional. His poems often reflect a sense of longing or melancholy, as he meditated on the transient beauty of the world around him. In this sense, Kunai-kyō can be seen as an early precursor to later poets, such as the famous Bashō, who would continue to explore similar themes of nature, impermanence, and the fleeting moments of human life.

Kunai-kyō’s Legacy and Influence

Kunai-kyō’s influence on Japanese poetry, while not as widely recognized as that of poets like Fujiwara Teika or Bashō, remains significant. His work reflects the shift in Japanese society during the 13th century and provides a valuable window into the intersection of courtly life, Buddhist thought, and the changing social landscape.

His poetic contributions helped shape the development of waka as a medium for personal expression. His themes of impermanence and his introspective tone influenced later generations of poets, particularly during the Kamakura period and beyond. While Kunai-kyō’s legacy may not have been as prominent in the public consciousness, his role in shaping the direction of Japanese poetry should not be underestimated.

Conclusion

Kunai-kyō, a 13th-century Japanese poet, remains an important yet somewhat overlooked figure in the history of Japanese poetry. His works, deeply influenced by the cultural and political shifts of his time, offer a poignant reflection on the impermanence of life and the fleeting nature of beauty and human experience. While his poetry shares thematic concerns with his contemporaries, such as Fujiwara Teika and Jien, Kunai-kyō’s introspective, emotionally resonant style sets him apart as a unique voice in the world of 13th-century Japanese poetry.

By examining Kunai-kyō’s work within the context of the broader literary tradition of the time, we gain a deeper understanding of the evolution of Japanese poetry and its engagement with the social and spiritual currents of the era. His legacy, though less celebrated, provides invaluable insights into the shifting cultural landscape of Japan during the 13th century.